What's the big picture for U.S. drought in fall 2017?

This year, especially this last quarter, has been a tough one on the weather and climate front.

With that said, one silver lining of a rough 2017 has been the general retreat of drought on a national scale. This spring, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the fraction of the contiguous United States in drought dropped below 10 percent for the first time since 2010.

However, with that said, since then, a severe drought emerged quickly in the Northern Plains this summer. As droughts go, this was a “flash drought”—rapid-onset, regional drought, driven by combination of factors, typically during the summer.

Drought conditions across the United States as of October 3, 2017. While there was plenty of yellow—abnormally dry conditions—spread over the map, less than 10% of the country was experiencing full-blown drought of some kind. And only the plains of eastern Montana were experiencing exceptional drought (darkest red.) NOAA Climate.gov image from our Data Snapshots map collection, based on data from the U.S. Drought Monitor project.

The early impacts of this drought episode were covered here on Climate.gov, and by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. The impacts, as you’d expect for a region dominated by livestock operations, are largely agricultural, although the fire season was also extremely active. But even beyond that, agriculture tends to be affected by drought fairly quickly, while other concerns—say, reservoir operations—have more of a slow trigger.

We get a lot of questions about the connection between events like this and the larger climate, and climate change in particular. The answer for now is direct: it’s too soon to know, it takes significant work to understand that connection, if there is one, and the “answers” when they come, if they come, are draped in probabilistic statements, like “X times more likely.”

But what we can do, immediately, is provide context. So here we go.

Did you know that we’re in one of the droughtiest eras of modern US climate history?

It’s true. A recent paper authored by my colleague Richard Heim objectively identified three major national-scale drought episodes in modern U.S. history. Two are well-known to all: the 1930s “Dust Bowl” era, during which drought emanated episodically from a Central Plains epicenter, and a large drought in the Southern U.S. during the 1950s. The third episode is marked by recurrent droughtiness of the western United States during the 21st century—since 1998, to be exact.

Drought coverage, shown as percent area of the contiguous United States and calculated using the Palmer Drought Severity Index, since 1900. The lighter shade shows the coverage of moderate to extreme drought, and the darker shade shows severe to extreme drought. The dotted line is a lagged five-year average of the severe-to-extreme category.

Richard wrote a pretty important, and quite practical paper. It will reset a little bit about what we know about observed droughts in our history, and lay out a set of tools to compare and contrast past and future droughts.

If drought has gone away in 2017, is this drought era over?

The short answer is: ask me in a couple of years and we’ll know the answer. I hope that doesn’t seem flippant, but it’s the reality of the creeping, incipient nature of drought. It’s hard to recognize when they begin; it’s also really challenging to determine if an apparent recovery will be short and transient, or more lasting.

Back to Richard’s paper. Some key distinctions between the recent drought era and the two 20th-century eras are: the 21st-century drought era has lasted longer than the other two; the 21st-century drought era has been somewhat more western than the other two, and the 21st century drought has been “wetter” than the other two.

Wetter drought?

Yes. All drought eras, and even smaller and shorter drought episodes, are marked by starts and stops, expansions and intensifications, retreats and marginal improvements, and often some “false recoveries.” The 1950s drought era was easily the most consistent, persistent of the bunch, but even it had seasonal and regional variations.

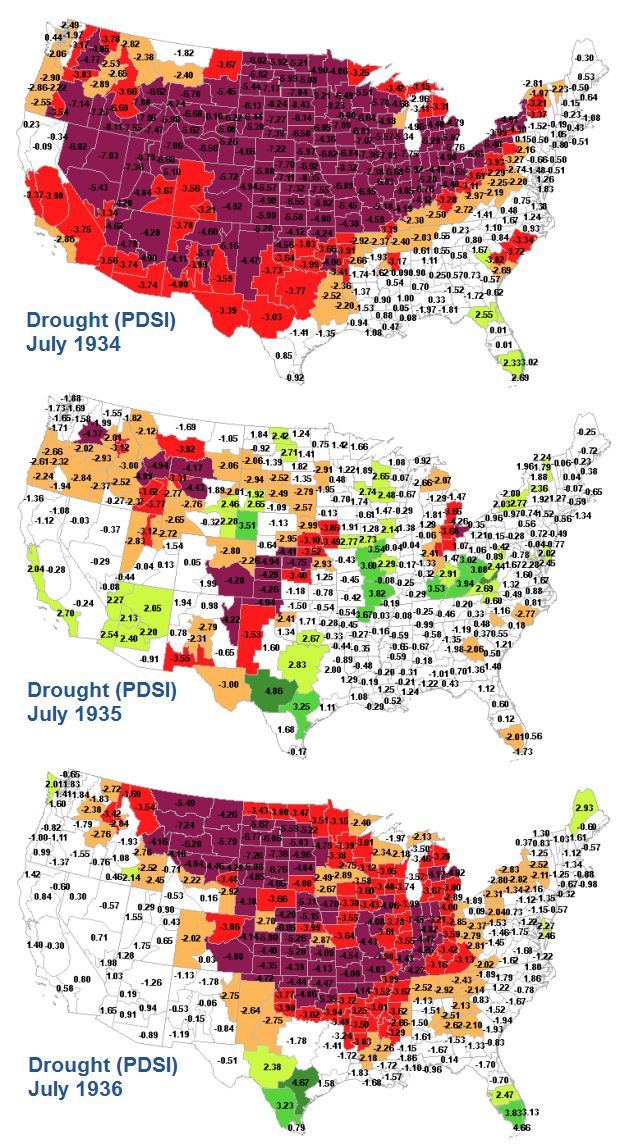

Drought, as measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index, for three consecutive Julys: 1934, 1935, 1936. Drought ebbed and flowed within one of the most prolific drought eras in modern American history.

This 21st-century drought era has been wetter in the sense that the temporary interruptions have been much stronger. Large chunks of the drought’s footprint have been temporarily—and by temporarily, this climatologist means “several seasons”—erased by very wet periods. In other words, instead of just eating away at the edges, temporary recovery comes to large areas, which get drenched with historically significant wet spells.

And yet, despite the whopper wet punches, the overall pattern has returned, so far, to large-scale drought, affecting large parts of the country. Even when drought has been pushed out of most of the West, large regional droughts in other parts of the country have kept the drought footprint going while the West temporarily enjoyed wet times.

So, how will drought change with the climate?

Drought is a complex thing. It occurs when moisture supplies are interrupted, often by large, slow atmospheric features that reroute historically normal moisture pathways away from a region over weeks to months to years. There is some evidence that these larger, slower, more persistent meteorological patterns are becoming more prevalent than, say, last century, and that they will increase the runs of rain-free days in the Plains.

It's still an active area of research, but the research is moving pretty quickly on this. In terms of climate change’s role in changing those larger scale patterns, we’re not far away from knowing a lot more.

Pulling back from the drivers of precipitation patterns that give rise to drought, here’s a safe assertion: a warmer atmosphere is a thirstier atmosphere, demanding more water from surface water (rivers and lakes and their smaller cousins, creeks and ponds), and more water from the soil, directly and through plants and crops.

Part of the 160,000-acre Rice Ridge Fire in central Montana on September 3, 2017. Drought contributed to an extremely active fire season in the state in summer and fall 2017. Photo courtesy Inciweb fire information website.

That takes us all the way back to the “flash drought” concept and our current Northern Plains episode. Flash droughts tend to be warm-season events because one key ingredient for rapid drought onset is a lot of warmth. Mild, rain-free days may eventually lead to drought. But hot, rain-free days lead to drought a lot faster. In this sense, as the warm season warms and becomes longer, this kind of rapid-onset regional drought is likely to become a bigger part of our future.

Comments

Add new comment