A new assessment from a NOAA-led task force has concluded that the unprecedented drought parching the U.S. Southwest since 2020 is not entirely natural.

The team found that the record-low precipitation that kicked off the event could have been a fluke—just the rare bad luck of natural variability. But the drought would not have reached its current punishing intensity without the extremely high temperatures brought by human-caused global warming.

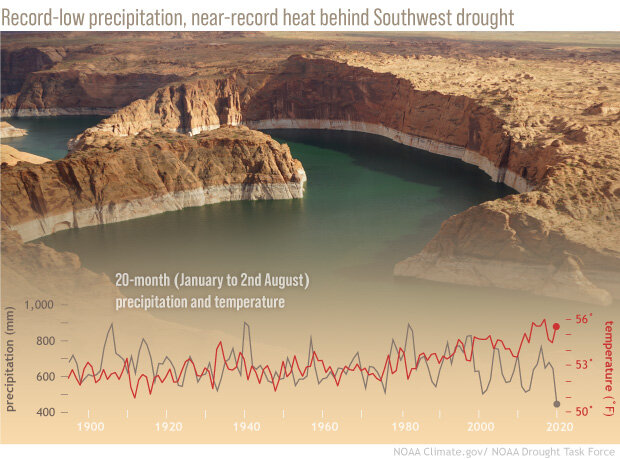

Cumulative precipitation (brown line) and average temperature (red line) for all 20-month, January–August periods since 1895. The current drought coincided with record-low precipitation and near-record high temperatures. NOAA Climate.gov, adapted from original by the NOAA Drought Task Force. Photo of low water levels in Lake Powell on August 13, 2017, by Flickr user Edwin van Buuringen, used under a Creative Commons license.

As part of their analysis, the team compared observations of precipitation and temperature across six southwestern states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah—for the 20-month period from January 2020 through August 2021. Many areas in the region experienced three successive “failed” wet seasons; the 2019-2020 winter wet season, the 2020 June-August North American monsoon, and the 2020-2021 winter wet season were all below average.

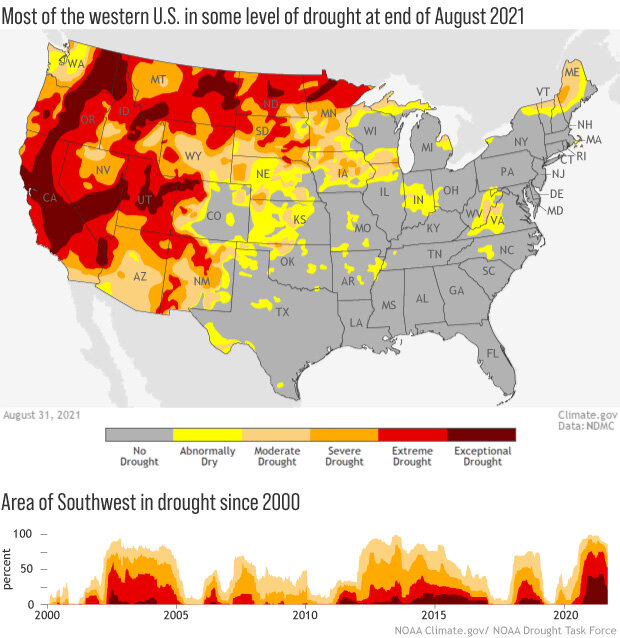

Although the 2021 summer monsoon was good—well above average in some places—it was not enough to counter the cumulative shortfalls of the preceding years. The cumulative precipitation for the 20-month period was the lowest on record, dating back to 1895. That left almost the entire western half of the contiguous United States in some level of drought at the end of August.

(top) Drought conditions across hte contiguous United States at the end of August 2021. Most of the West is in some level of drought. (bottom) Percent of the Southwest in different categories of drought since 2000. Map by Climate.gov, based on data from the U.S. Drought Monitor project. Graph adapted from original by the NOAA Drought Task Force.

Meanwhile, the average temperatures over the same 20-month period were near-record high. High temperatures make the atmosphere thirsty for moisture, which it draws vigorously out of the region’s soil, rivers, lakes—even the snowpack. This atmospheric demand, called a vapor pressure deficit (“VPD” for short), reached record highs during the current drought. Based on an analysis of computer model experiments, the drought task force team concluded that without efforts to control human-caused global warming, we should consider the current extreme drought a preview of coming attractions for the region:

By 2030 and with no climate mitigation, more than 1 in 10 years will have VPD values as high as 2020…and by 2030–2050, a decade with VPD as high as we have seen in the last decade (2011–2020) will be the norm… .

Exactly how devastating these conditions will be in different parts of the Southwest will depend on regional and seasonal variability in future precipitation as well as the decisions people make about how to manage the region’s scarce water resources. But the current drought suggests that the costs will be steep and the impacts far-reaching. The NOAA Drought Task Force estimated that the 2020 economic cost of drought in the Southwest was between $515 million and $1.3 billion—not including the costs associated with fires.

As for when the current event will break, the task force warns that it’s unlikely to be this winter. Thanks in part to the expectation that La Niña will settle into the tropical Pacific by later this fall, odds are that winter precipitation across the Southwest will be below average once again. That means the drought will likely persist well into 2022, and perhaps longer, depending on how unfavorable the coming wet season is.

The work of this NOAA Drought Task Force was funded through a collaboration between the National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) and the MAPP program of NOAA’s Climate Program Office.