This article was updated Friday, March 8, to include details about climate influences beyond temperature, and on March 11 to include a quote from climate impacts & policy expert Katharine Hayhoe.

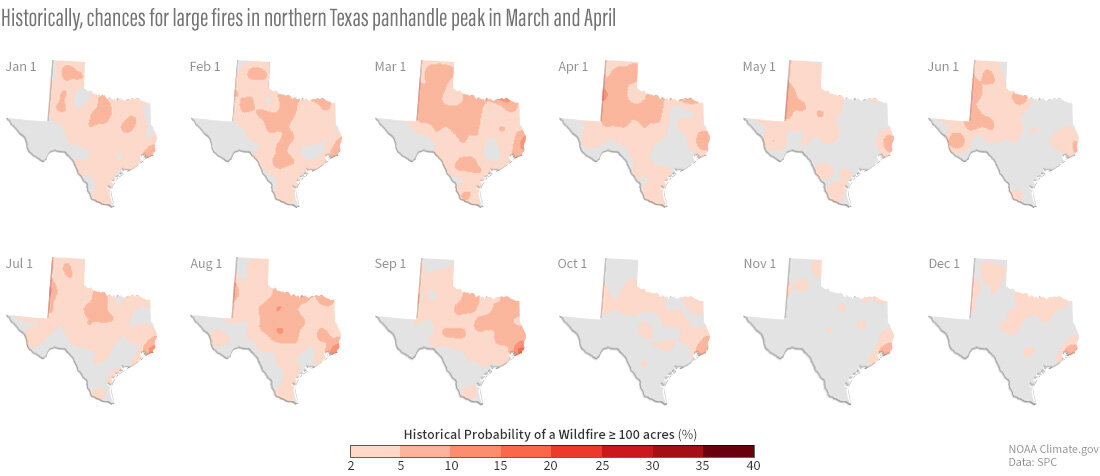

In the last week of February 2024, a record-setting fire outbreak charred its way through the northern panhandle of Texas. Climatologically speaking, it was right on time: the grasslands of the southern Great Plains historically face their highest fire risk in late winter and early spring. Grasses are still dormant and dry, but temperatures are starting to climb.

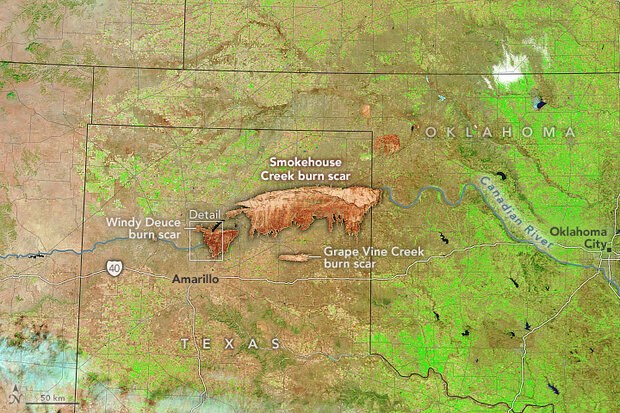

Satellite image of burned areas (reddish brown) north of Amarillo, Texas, on March 2, 2024. Olive-brown areas are grass-dominated landscapes where vegetation is dormant for the winter. In the fire area, the bright green vegetation is irrigated fields. NASA Earth Observatory image.

Aside from the timing, though, the outbreak of megafires—those larger than 100,000 acres—was something of a surprise from a climate perspective. Historically, Texas’ worst fire seasons have occurred following La Niña winters, which tend to be warmer and drier than average across the southern United States. This winter, by contrast, has been under the influence of El Niño, and the northern panhandle of Texas was wetter than average in December and January. That pattern did change in February, but even so, the February 20 Drought Monitor map was empty of drought or even “abnormally dry” conditions in the area where the outbreak began on February 26.

But that’s the thing about fire in the Southern Plains that can be counterintuitive, explains Todd Lindley, a NOAA forecaster who specializes in fire weather on the Southern Plains. “Here, a very deep drought actually reduces the fine fuel loading on the landscape.” What’s more dangerous is a wet spring and summer growing season. “You grow more grass, and then you get into the winter and [early] spring dormant season, and those fine fuel loadings are vulnerable to fires.”

Daily chances of a fire 100 acres or larger with 25 miles of a given location based on data from 1992-2015. NOAA Climate.gov maps, based on data from the NOAA Storm Prediction Center. View maps for each day of the year in our Data Snapshots collection.

In other words, it doesn’t take drought to prime the prairie for a blaze. “Because the fire spread is really facilitated by these finer, grassy fuels,” Lindley said, “you can dry them out just very, very quickly.”

Even knowing this, Lindley admits, he was surprised by how quickly conditions deteriorated. On February 21, Lindley and his colleagues first reported to an interagency group of stakeholders through an online fire-risk forum that a weather system of concern was approaching the area. At that time, he says, values on an index they use to estimate the condition of vegetation and how much heat it could release if burned were well below the 50th percentile. “In less than a week,” Lindley says, “they were locally exceeding the 80th percentile,” meaning in the highest 20 percent on record.

There was essentially no gradual build up in fire activity like they would normally see, with a few smaller fires gradually increasing in number over a two- to three-week period leading up to a major outbreak. “We had one fire of about 4,000 acres on February 24 near Amarillo,” Lindley says. “That was really the only indicator that the environment was trending to a more vulnerable state” before the explosion in fire activity on February 26.

“I’ve been doing fire here in the Southern Plains for 17 years, and that is probably the most rapid degradation of the fuels that I have seen,” Lindley says.

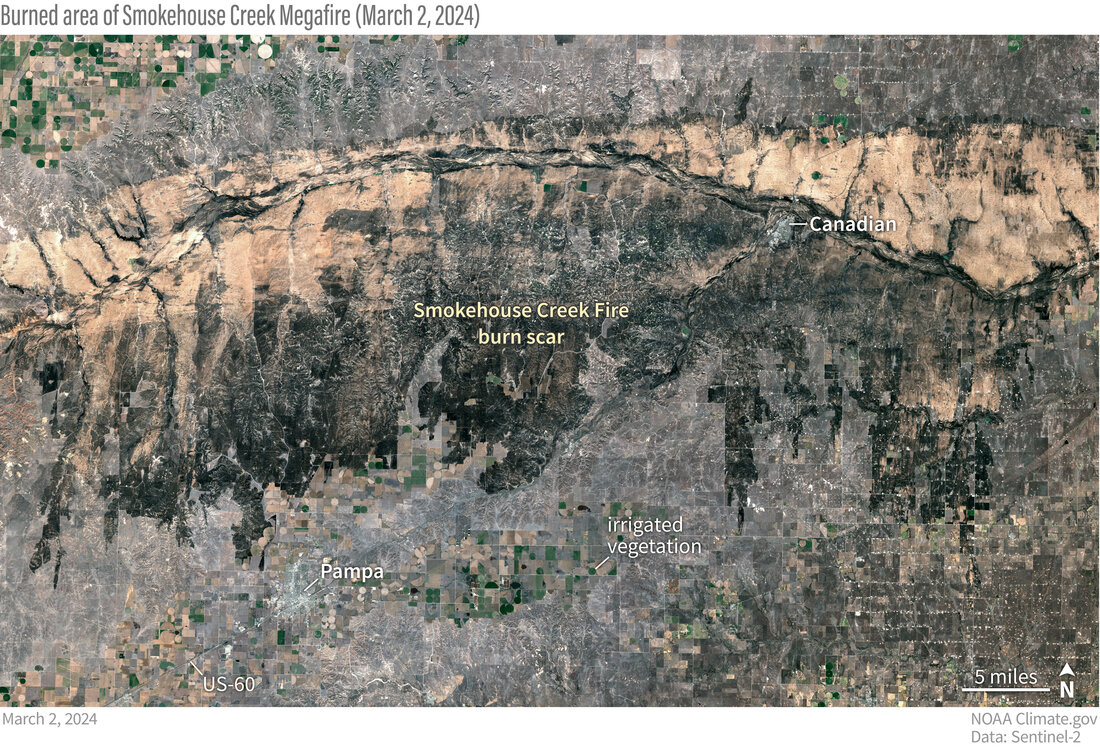

Satellite image of the area burned by the Smokehouse Creek fire northeast of Amarillo, TX, on March 2, 2024. Image based on modified Copernicus Sentinel-2 data from the Sentinel Hub EO Browser.

Fire suppression and climate change in the Southern Plains

Like other parts of the West, a century of fire suppression policies have left the Southern Plains with an excess of fuels. Lindley says, “The fire suppression has allowed an invasion of short, woody species like eastern red cedar and mesquite. What used to be well-managed by Native Americans as a grass prairie is becoming more of a mixed ecosystem, with grass that facilitates very rapid fire spread, but you also have these low-canopy wooded species that increase the fire intensity dramatically.”

A fire burning in South Dakota on April 9, 2017. Invasive Eastern red cedar trees give prairie fires an intensity that grass alone would not produce. Photo courtesy USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service Flickr. Used under a Creative Commons license.

There’s no denying the impact these choices have had on fire behavior in the Southern Plains. Says Lindley. “We had over-suppression for well over a century, and now, even though if you look at the total number of fires, they’re on a decline, but the fires that we do get, are growing in size and intensity almost exponentially.”

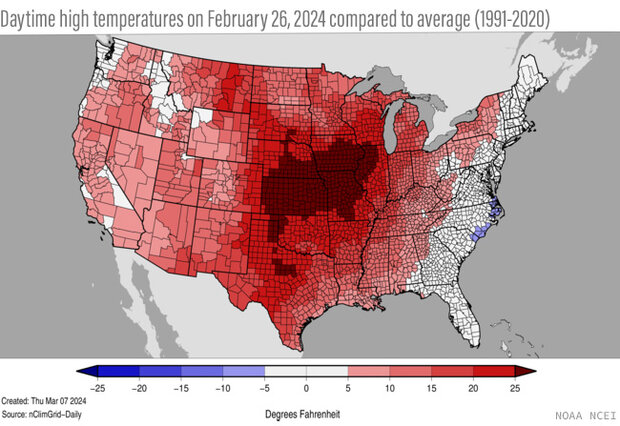

The legacy of fire suppression is a key part of the story. At the same time, the late February weather system that primed the prairie for fire had at least one stand-out characteristic: heat. “On Monday, the 26th,” says Lindley, “when the fires initiated, we were seeing record-high temperatures across central and west Texas and western Oklahoma.”

Daytime high temperatures across the Great Plains were 20 degrees of more warmer than average on February 26, the day the fires broke out. NOAA image from National Centers for Environmental Information.

Without a specific type of analysis called extreme event attribution, it’s impossible to say exactly how much influence long-term global warming had on this event. But we know winters in North and West Texas are getting warmer, and new heat records are being set more frequently today than they used to be. Unless precipitation or humidity increases enough to make up for them, higher temperatures increase evaporation and dry out plants and soil. Over land areas, increases in moisture haven't kept pace with increases in temperature.

"Relative humidity over land is generally projected to decrease in a warming climate," explained John Nielson-Gammon, Texas state climatologist and director of NOAA's Southern Regional Climate Center, via email. "But even if it were to stay the same, higher temperatures mean a greater difference between the amount of moisture in the air and the total capacity of the air to hold moisture." The imbalance makes the atmosphere thirstier, increasing evaporation.

He continued, "This temperature effect is strongest under the very low humidity conditions that occur during days of high fire risk in West Texas. So the direct effect of climate change on temperature would have allowed the fuels to dry more quickly and to a greater extent, increasing the intensity and rate of spread of any fires that developed."

As far as other ways climate change might have affected fire ingredients, things aren't as clear cut as they are for temperature. Says Nielson-Gammon, "Overall rainfall trends are almost zero in the Texas Panhandle, so climate change probably didn't affect the amount of fuels from a rainfall perspective." Some possible influences are even more complicated. Climate change could influence plant productivity in competing ways. Have higher amounts of carbon dioxide had a "fertilizing" effect on grass growth? Have warmer temperatures extended the growing season, or are the Southern Plains too rainfall-limited for that to matter? As for whether the high-wind, low-humidity weather patterns that set the stage for fires might become more or less common, "the scientific jury is still out."

Despite those open questions, the influence of warming itself is clear: it's tipping the scale toward more severe fire weather. According to the Fifth National Climate Assessment,

From 2000 to 2018, firefighters in the Southern Great Plains fought 16 megafires—fires that encompass over 100,000 acres, overwhelm local response capacity, and are extinguished only when weather conditions become favorable. These fires are associated with extremely dry vegetation, unusually warm temperatures, and strong winds aloft—conditions projected to become more prevalent as the region warms and soil water evaporates more quickly.

One analysis projected that with high greenhouse gas emissions, warming by the middle of the century would increase the risk of very large fires in the Southern Plains by up to 50 percent.

Protecting people, livestock, and property in a warmer world

The ultimate solution to increases in dangerous fire weather is to stop global warming; the world must bring the net amount of greenhouse gases that we release into the atmosphere down to zero. That won’t happen immediately. But naturally occurring fire is part of the Great Plains ecosystem, regardless of climate change, which means that taking steps to make landscapes and communities in the Southern Plains more resilient to climate extremes and fire will have benefits no matter what.

Via email, Andrés Cibils, Director of the USDA Southern Plains Climate Hub, commented, “Adaptation planning has proved to be an effective approach to increase wildfire disaster preparedness. The USDA Climate Hubs in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service have generated detailed protocols for assessing fire vulnerability and developing adaptation plans. Practical preparedness strategies are available through the Texas A&M Forest Service website, and wildfire forecast tools such the Fire Danger Viewer, developed by USGS and the US Forest Service, are intended to assist agricultural producers with both long- and short term wildfire adaptation planning. Additional wildfire risk and forecast tools are available on the USDA Southern Plains Climate Hub website.”

Planning for fire can be part of a comprehensive strategy with multiple benefits. Via email, climate impacts and policy expert Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University and Chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy, wrote, "For too long, our stewardship of the land has been short-sighted. We've neglected the long-term consequences of our management practices, and the consequences of that choice are affecting us today. It’s time to consider both the near-term and the longer-term benefits of natural climate solutions including smart grazing, ranching, and farming practices. These practices can not only restore ecosystems but also improve soil and water quality, sequester carbon, boost agricultural yields, and bolster our resilience to climate impacts. They’re win-wins for people and the planet."

More fire resources

- The Climate Program Office’s Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program (SCIPP) assists organizations with decision making that builds resilience by collaboratively producing research, tools, and knowledge that reduce weather and climate risks and impacts across the South-Central United States.

- NOAA’s Wildfire Resources page highlights NOAA forecasting and fire science research.

- NOAA’s Southern Regional Climate Center works to provide climate data services to fulfill a wide range of applications for the States of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas.