Coral Bleaching Could Be As Severe as 2005 Event

Details

The rising temperature of the world’s oceans has become a major threat to coral reefs globally. In unusually warm waters, corals can bleach, expelling the symbiotic algae that produce much of their food. Not only do their vibrant colors to fade to white, but if thermal stress is sustained, bleaching may lead to disease, starvation, and death.

In the summer of 2005, ocean temperatures in the tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean exceeded average temperatures seen over the past 150 years. These conditions resulted in the most severe coral-bleaching event ever recorded in the region. In all, 80 percent of corals bleached and more than 40 percent were killed by a combination of bleaching and disease outbreaks at several sites in the Caribbean. In late summer 2010, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Program forecasted that the bleaching threat for the Caribbean through the end of the year had the potential to be as bad as or worse than it was in 2005.

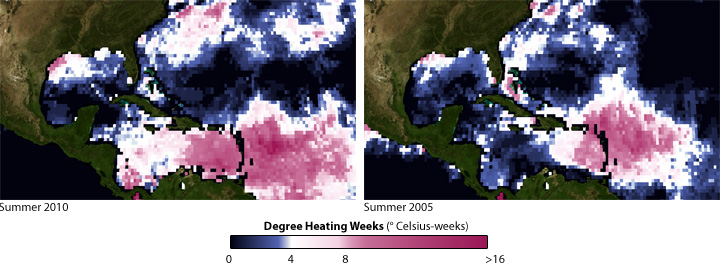

The maps above show the accumulated coral heat stress in the tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean during a 12-week period ending September 30, 2010 (left) and 2005 (right). Areas shown in dark blue have not accumulated thermal stress over the previous 12 weeks, meaning that the temperature had not crossed the local bleaching threshold. Shades of pink indicate areas where corals experienced a build-up of thermal stress that was enough to cause significant bleaching (light pink) or mass bleaching and death (dark pink).

To estimate heat stress on corals, NOAA scientists multiply the sea surface temperature anomaly (how many degrees Celsius the temperature is above the area’s normal summertime maximum) times the number of weeks the anomaly lasts. Two °C-weeks is an amount of heat stress equivalent to 2 weeks with temperatures 1° Celsius above the normal maximum. (The same amount of stress may build up in 1 week if temperatures are 2° C above the normal maximum.) Values above 4°C-weeks cause significant bleaching, while values above 8°C-weeks can cause mass bleaching and death.

In 2005, many areas of the Caribbean experienced sustained thermal stress exceeding 16°C-weeks, well above the stress levels that cause coral death. Extremely warm waters in the Virgin Islands resulted in 90 percent of the area’s corals being bleached. Weakened from the event, 60 percent later died from disease. (For more information, see the ClimateWatch article, Hope in the Face of a Caribbean Coral Crisis).

As of the end of September 2010, large areas of the southeastern Caribbean Sea were experiencing heat stress similar to conditions in 2005. This year, however, warmer waters are more widespread throughout the western Gulf of Mexico and the extreme southern Caribbean Sea. Coral reefs in the Virgin Islands, which are still recovering from the 2005 event, are being spared some of the worst bleaching conditions. Unfortunately, the famous coral reefs surrounding the islands of the Dutch Antilles off the Venezuelan coast are seeing more stressful conditions than they did in 2005.

Corals weakened by bleaching can recover if the waters cool enough to allow the surviving microalgae to reproduce. But many corals succumb to coral disease, starvation, and local threats. As global ocean temperature continue to rise, coral reef managers hope that protecting coral reefs from local pressures like overfishing and water pollution will enhance their resilience to climate change and prevent dramatic declines in valuable coral reef resources.

Maps based on degree heating week data from NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Project.

Related links:

Hope in the Face of a Caribbean Coral Crisis

NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Project

NOAA: Coral Bleaching Likely in Caribbean This Year