Talking with IPCC Vice-chair Ko Barrett: On climate change and consensus building

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently released a special report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. This report investigates the impact that 1.5°C of global warming will have on the people, plants and animals that call Earth home and the pathways to limiting warming. The report was a request in the Paris Agreement, driven by the concerns of many countries, especially in the Pacific Ocean, who could feel disproportionate impacts from warming below the 2°C threshold the climate negotiations have established as a target.

Before and after images of heat-stress related coral bleaching in American Samoa, in the tropical Pacific. The left image was taken in December 2014. The right image was taken in February 2015. Coral reefs, which provide food, livelihoods, and storm surge protection for many island communities, are among the natural resources that are very likely to experience severe impacts from less than 2°C of warming. Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

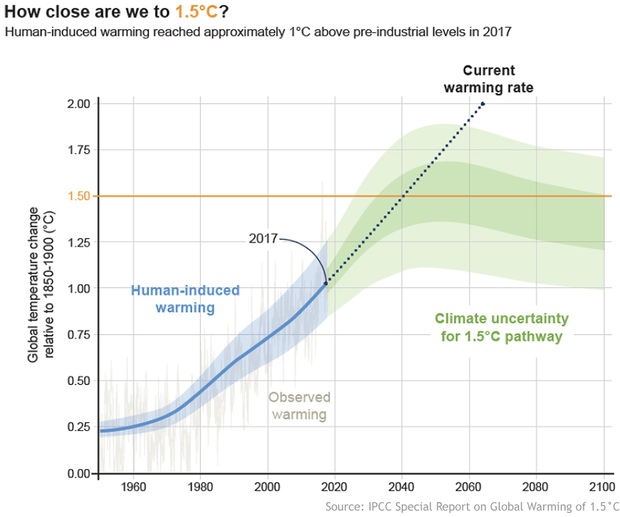

In the report, the IPCC concluded that Earth has already warmed approximately 1°C compared to pre-industrial times, and if warming continues at its current pace, we will reach 1.5°C of warming within 1-3 decades (2030-2052). Limiting warming to 1.5°C is not impossible but would require unprecedented transitions in all aspects of society. Additionally, the IPCC found that limiting warming to 1.5°C can go hand-in-hand with achieving other world goals, like achieving sustainable development and eradicating poverty.

To learn more about this report and the process that created it, I talked with Ko Barrett, a Vice Chair of the IPCC, based in the U.S. Ms. Barrett, who is also Deputy Director of NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Office, has been working on climate for over two decades, representing the United States as a climate negotiator, including almost a decade as the lead U.S. negotiator on adaptation.

Ko Barrett (right) and Vice-Chair Thelma Krug (left) at the plenary session of the 45th Session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in Guadalajara, Mexico on March 28, 2017. Photo by IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera.

Now in her capacity as Vice Chair of the IPCC, she has helped bring this report together, convening groups to bring about consensus. We spoke by phone, and our conversation has been lightly edited.

Thank you for your interest. Since 2001, I had been a U.S. delegate to the IPCC as part of the U.S. government delegation. In 2015, elections were being held for the new leadership team of IPCC. The U.S. had always had a spot on the leadership team, so they put me forward for vice chair, and I was elected by acclamation.

There are 12 people who compromise the IPCC leadership team. A chair, three vice chairs and two co-chairs for each of the four working groups or task forces. The chair is the main representative for the organization. The co-chairs produce the reports and do the bulk of the assessment work. The three vice chairs sit in-between those two levels. We assist with representational activities and work, especially during approval sessions, to convene groups to reach consensus on language.

We also do various other things. In my case, I am the lead for the science board that runs the scholarship program that we fund with the Nobel Peace Prize money that we received in 2007. The program is geared specifically to recipients from developing countries.

The IPCC was formed in 1988 when the issue of climate change was just emerging as a possible challenge. It is unique in that it is a scientific assessment body that is intergovernmental in nature. It is sponsored by two organizations in the United Nations (UN) system: the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the UN Environment Program. So the way it functions is like nothing else.

We produce periodic assessments of the state of climate or special topics of interest to policy makers. We commission a host of volunteer scientists/authors across the globe that have expertise in the issues we are covering in our assessments. At various stages of production of the report, we put it out for expert and government review.

IPCC delegates discuss new text during a meeting of a contact group for special reports during the 43rd Session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC-43) in Nairobi, Kenya, on April 13, 2016. Photo by IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth.

The governments don’t actually negotiate the main body of the report. That is accepted by the governments. But the summary for policymakers is negotiated line by line and approved by governments. This is a way to give the governments a chance to weigh in on the report, both generally and specifically. The summary for policymakers is a discrete enough piece of the report to actually negotiate with governments, without having to put the whole thing up for negotiation.

It [the IPCC] is this incredible handshake between scientists and decision makers that makes it an authoritative perspective on climate science like no other.

This report is on a specific question: the impact of 1.5°C of human-caused global warming. What was the significance of that and how did that come about?

Since its inception, IPCC has provided science to the climate negotiations at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Every time we put out a report, we’ve briefed it to the climate negotiations, and they take it up as an agenda item to see if there were elements that are illuminated through the science that should be considered as they set global policy [for participating countries].

In this particular case, for the first time ever, the UNFCCC, through the Paris Agreement, requested IPCC to do a report specifically in service of this policy discussion.

You may be aware that the Paris Agreement has a temperature target to keep temperature change well below 2°C [compared to pre-industrial conditions]. That is very much an estimation of where the global policy community believes there is a threshold for global risk that should not be exceeded.

In those conversations, however, there have been a subset of countries, like the Pacific Island nations, that have been pushing for a lower temperature target—1.5°C— because they believe that the threats from sea level rise and from other climate impacts are actually going to be affecting their lives and livelihoods, in the near-term, at a temperature threshold lower than 2°C.

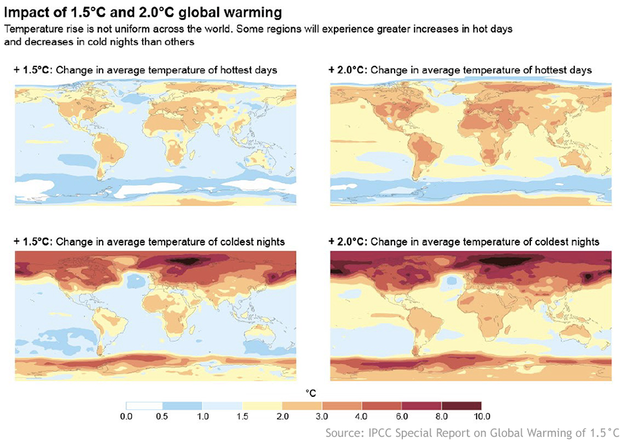

Temperature change is not uniform across the globe. Projected changes are shown for the average temperature of the annual hottest day (top) and the annual coldest night (bottom) with 1.5°C of global warming (left) and 2°C of global warming (right) compared to pre-industrial levels. Graphic appears in FAQ 3.1 in the Frequently Asked Questions supplement to the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

The Paris Agreement, and the UN by association, asked us to look at the science behind what the impacts would be at 1.5°C, and what kinds of emission pathways we would need to be on in order to limit the warming to 1.5°C. We accepted that invitation to do that report and had to turn it around in a pretty quick timeline.

The report is the outcome of 91 dedicated lead authors and review editors from 40 countries along with 133 contributing authors. These authors assessed more than 6000 scientific publications for this report. And in the various expert and government review stages, we received 42,000 comments from more than 1,000 experts worldwide!

And, I’ll tell you an interesting thing that we didn’t realize was going be one of the major messages from this report. As the authors were crafting their report, they were tasked with comparing 1.5°C to 2°C. But, in order to provide the proper context, they had to compare 1.5°C to where we are now. This information lets people know that we have already experienced 1°C of warming. And it has become very clear that every bit of warming matters.

Another interesting thing about this report has been how well it has been communicated, including the figures.

We’ve gotten the message loud and clear from our previous assessment reports that sometimes, even in our attempts to be understandable to policy makers, we speak too much in a scientific jargon. So this round, every one of our working groups had at least one communication specialist working with them all during the course of the development of the report. Not just at the end to translate the story into something understandable, but throughout the process to improve the readability of the report. We also hired graphics experts to help us tell those stories better. In the past, we have sometimes had captions for figures that were an entire page long with all kinds of acronyms.

Human-induced warming (blue shading) reached approximately 1°C above pre-industrial levels in 2017. At the present rate, global temperatures would reach 1.5°C around 2040. Stylized 1.5°C pathway shown here (green shading) involves emission reductions beginning immediately, and CO2 emissions reaching zero by 2055. Graphic appears in FAQ 1.2 in the Frequently Asked Questions supplement to the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

I’ve always been curious what goes on in the trenches working on such a massive science report. What is going on inside those rooms?

Whatever can be addressed to agreement in plenary session (the main meeting of all of the countries delegations and the observer organizations to the IPCC) is done there, because you have to be incredibly cognizant that there are some folks, especially from the least developed countries, who do not have large delegations to deploy to a bunch of different breakout groups in order to reach agreement.

Issues that aren’t resolved in plenary go into an informal huddle just outside the main room to see if it is a quick fix. These can be times where you are just finding the words that hit that sweet spot for consensus. For more complicated things, it will go into a contact group that is facilitated by a couple of chairs to work through the whole range of issues. That is a role that I play quite often because I have two decades of experience as a negotiator.

The one thing I do quite well is to work to find consensus. In that room, we will take the problem piece by piece. Whatever it is. The facilitator will see what the issues are that are causing concerns and look for compromise language, always checking with the scientists to make sure that whatever is being proposed [by the political delegates], and eventually agreed to, is in with keeping with the science of the report.

This is not just a science report but an intergovernmental report that has to be signed off by all of these countries.

Exactly. And at the meeting, it is sometimes challenging for scientists to let the governments debate about what language is representative without jumping into that debate themselves. The scientists are consulted to see if what is coming from this intergovernmental conversation is correct, scientifically, but it is hard to bite your tongue from saying, “No, that’s not the way I want to say it.”

Were scientists biting their tongues all over the place?

[Laughing] I know that in the past, there have been stories about times when governments have changed the draft in ways that infuriated scientists. But in this case, and I heard this directly myself, scientists, because they were so integral to checking the language, felt that the intergovernmental process improved the draft.

But, there were some difficult areas. There is a portion of the report that assesses the pledges [for emissions reductions] the governments made in Paris, and it concludes that those are not enough to keep warming below 1.5°C. Now, the IPCC has a mandate to be policy relevant, but not policy prescriptive, so there was a debate to carefully craft the language [in this section of the report]. By and large, though, most of the issues were pretty readily resolved.

By and large, though, most of the issues were pretty readily resolved.

In your experience, what have you learned about reaching consensus?

I am a strong believer that there are many pathways to consensus. And my particular approach that works well for me may not work well for someone else who has a different intuitive approach.

Ko Barrett (center) talking with IPCC Vice-Chairs Youba Sokona (left) and Thelma Krug (right) at a meeting on March 15, 2018, during the 47th Session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in Paris, France. Photo by IISD/ENB | Mike Muzurakis.

Good faith negotiating is the something I learned through the negotiations. If you have a tough position, it’s just important to put it out there, be very clear with people what it is and then work to find compromise on the edge of that. Rather than obfuscating where you are and not being a good, honest broker.

Those are skills you bring to any kind of compromise situation, whether it’s in the workplace, your family, on an athletic team.

Just go with your intuitive gut.

Copenhagen was a very high profile meeting. It was 2009. Expectations were very high for us to reach an agreement. President Obama flew in, and flew out in a snowstorm. We thought we had agreement, and in the middle of the night, after President Obama and many of the world leaders left, the agreement fell apart. Because you have to reach consensus and there were a group of countries that would not agree. So that was a low point.

The next major meeting was the COP (Conference of the Parties) in Cancun [2010] where expectations were quite low. We were all quite frankly wondering whether or not the institution would remain viable because it was such a low moment in Copenhagen. But the Mexican presidency did a FABULOUS job of making sure issues were well socialized, and bringing people in. They were just extraordinary. And we reached agreement in Cancun, which was an incredible high point.

Last year, President Trump said that he will pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement. What does that mean for the U.S.’ involvement in the IPCC process?

To date, the U.S. has remained involved, and the U.S. continues to provide a large percentage of the scientists who volunteer their time to produce the reports. There has not been any indication that the U.S. is going to pull out of the IPCC process [Interviewer note: The Paris Agreement is a treaty that is part of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It is not the same thing as the IPCC, which is the body of scientists and government delegates that assesses and reports on the state of the science on climate change.]

I think you have to be an optimist when you work on climate. It is a long-term problem. It is not going to be solved overnight. And it takes the global community working together. It’s just the small successes over time that keep you going.

I think the young me would be amazed that I get to work on this international stage on such a complex problem with people from different cultures, who I learn from every day. And I have this global perspective that I never dreamed I would have as a kid growing up in New Jersey in a family where no one had ever traveled outside the U.S.

And the other thing, as I’ve taken on my role at IPCC and also at NOAA, is that, as a woman leading an organization it is so gratifying to have women everywhere come up and ask me, “how did you get this to work for you” and to be able to provide mentoring and encouragement, which is especially challenging in some countries where there is a gender imbalance for delegations.

I’m just so grateful I get play the role of mentor for women scientists.

That is such an interesting question! All my life, fall has been favorite season. But, now my favorite is spring. Spring in this area (Washington, D.C.) is beautiful. And now I’m a rower, so when spring comes around, I am getting back on the water and off the rowing machines of the winter.

[laughter] Well, I just got a puppy and now I’m very puppy focused.

Oh my gosh. It’s a kind of rare breed. It’s a Dutch retriever called a Kooikerhondje. Super cute. Look it up!

Thanks so much.