In the summer of 2023, portions of the Florida Keys experienced an extreme marine heat wave, unlike any other in recorded history for the region. Heat records were broken and some reefs were completely bleached—they expelled their food-producing algal partners and turned white.

Divers survey bleached corals at Cheeca Rocks reef at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary on August 1, 2023. Video produced by NOAA.

Throughout this prolonged heat wave NOAA scientists and partners raced to rescue vulnerable coral species, fearing mass mortality. Thousands of nursery coral colonies were relocated to climate-controlled labs, some were temporarily moved into deeper, cooler water, and small-scale shading experiments were conducted. In addition, live gene banking was also employed to preserve unique genetic individuals of threatened coral species.

(Read more about the adaptation and resilience strategies implemented last summer.)

The extreme ocean heat returned to more tolerable levels in the fall, although it was still above average. Previously relocated corals were returned to their original in-water nurseries across the Florida Keys. In February, NOAA’s Mission: Iconic Reefs program and their partners surveyed restored corals—which are nursery raised and outplanted on a reef—throughout the Florida Keys to better understand the impacts of the record-high ocean temperatures from the summer of 2023. The initial findings of this mission were pretty grim for some coral species.

Less than 22 percent of the about 1,500 outplanted staghorn coral remained alive across five of the seven Mission: Iconic Reef sites surveyed, according to a NOAA press release. A subsequent update showed that less than five percent of the about 1,000 outplanted elkhorn coral the experts surveyed were alive, Katey Lesneski, Mission: Iconic Reefs Coordinator wrote through email.

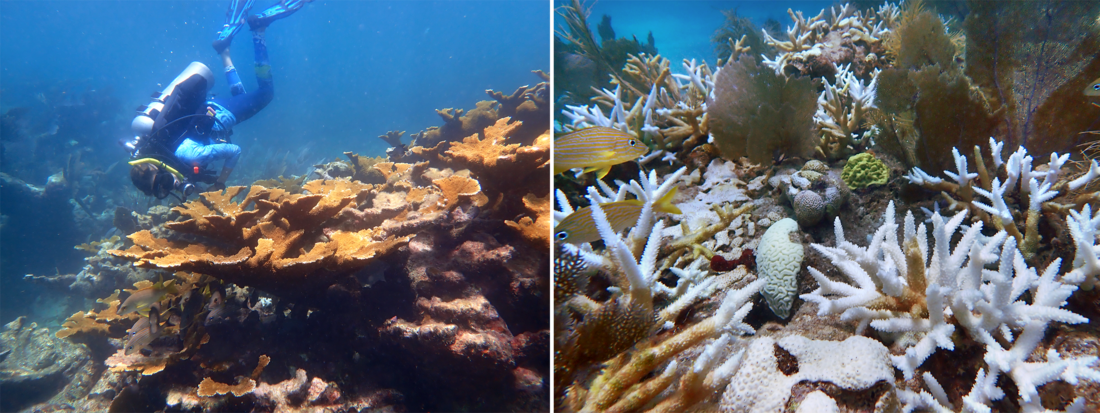

(left) Healthy elkhorn coral at Horseshoe Reef in the upper Florida Keys before last summer’s mass bleaching event. (right) Bleached wild and outplanted staghorn and brain corals at Sombrero Key Reef in the middle Florida Keys in the summer of 2023. Credit: Ananda Ellis/NOAA

Both staghorn and elkhorn coral are federally designated as threatened and protected under the Endangered Species Act. (A severe disease event in the early 1980s caused major mortality of both species and now less than one percent of their former population remains.) Now, warming oceans are the greatest threat to these coral species, according to NOAA Fisheries. Coral bleaching is projected to increase in frequency and magnitude as the oceans warm, according to NOAA Coral Reef Watch’s climate model-based predictions. Without intervention by coral practitioners this past summer, the region may have completely lost the last remaining wild elkhorn and staghorn corals in the Florida Keys ecosystem.

Lessons learned

Last year’s event forced a real-time experiment that showed which corals can survive and where. As they review the events of 2023, scientists remain hopeful for the future of coral restoration.

Alongside tremendous losses of elkhorn and staghorn coral, NOAA scientists and the many partners involved in the post-heatwave survey found many healthy and thriving wild and outplanted boulder, massive, and brain corals. Now they are planning to “dig into the data” to determine how and why those coral species fared better than the elkhorn and staghorn corals.

“Ghost Reefs” painted by Daniela Macaya, student at Yale University

Under Mission: Iconic Reefs’ restoration approach, the primary focus of initial efforts has been to restore elkhorn and staghorn corals because they grow relatively fast and have not been susceptible to stony coral tissue loss disease. The restoration of slower-growing stony corals—like brain, massive, and boulder—was planned for later and was just getting started. Now some reef specialists are considering shifting their focus to restoring more brain, boulder, and massive corals due to their survival success following last year’s extreme heat.

The losses at the Mission: Iconic Reef sites underscored the importance of prioritizing preservation of genetic diversity of remaining corals over mass relocations. During extreme events, reef managers expect there to be losses but by preserving genetic diversity reef managers can rebuild impacted reefs and nurseries following these events. Resources for mass nursery evacuations are limited and the losses of outplanted elkhorn and staghorn corals surveyed over the past year were significant. Due to these challenges, managers may consider being more purposeful with their limited resources, focusing on relocating and banking corals that have a higher chance of reproducing or those with unique genotypes–corals that may show more resistance to ocean heat, ocean acidification, or diseases.

Another piece of the puzzle that restoration managers are examining is timing and when it becomes essential to relocate any corals. They found that transportation can add significant stress to already heat-stressed corals and any movement should occur prior to significant heat events in order to maximize the likelihood of survival. In December 2023 NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch updated their satellite-based coral bleaching monitoring maps to include new risk categories, to better aid reef managers in making these challenging decisions. And last summer, NOAA launched a new ocean heatwave forecasting system. The system can forecast the size and intensity of ocean heat waves up to a year in advance for some locations of the global oceans, and up to several months in advance in other locations.

(Read more about NOAA's ocean heat wave forecasting system.)

Some adaptations and mitigation strategies such as shading, feeding bleached coral, and temporarily moving corals to deeper, cooler waters also showed some promising outcomes. Overall, having a rapid response plan in place, increased communication between relevant agencies, and quick access to support is also necessary for future severe coral bleaching events.

Mission: Iconic Reefs partners from Reef Renewal relocate corals from shallow water nurseries to deeper water nurseries during the 2023 summer heat wave. Video courtesy of Newman PR & Monroe County Tourist Development Council.

The future of coral restoration faces disagreement among some scientists

Despite all the forward progress being made in the realm of coral restoration, some scientists believe coral restoration efforts may be futile if ocean temperatures continue to increase. Some are asking, is it responsible to outplant coral species if mass die-off events continue to occur?

Phanor Montoya-Maya, Marine Biologist and Coral Restoration Foundation Program Manager, believes coral restoration is working, but future actions should be more deliberate.

Phanor Montoya-Maya dives at Pickles Reef in the Florida Keys. Credit: Coral Restoration Foundation™

“We cannot just go and outplant everywhere. Let’s go and check where we found some survivors and start identifying why,” Montoya-Maya said. “And then we can start adding corals there, and see if that pocket of survival can be expanded.”

He told us all approaches, both active and passive, should be enhanced and strengthened going forward. Active strategies refer to outplanting and growing corals and reefs, while passive strategies refer to improving water pollution, fishing regulations, and marine management.

Montoya-Maya stresses the importance of these passive strategies because they promote a healthy environment for corals and reefs to grow, so when a bleaching event does happen, the corals that survived by natural selection continue to thrive even after the event wanes, therefore further building resilience and adapting for the next bleaching event.

Montoya-Maya also urges patience.

“We need to be mindful that reefs take thousands of years to develop, corals take tens of years to grow into a large colony. Why are we expecting that whatever we do today, we need to see a result tomorrow? I think that is where we set ourselves up for failure.”

A healthy elkhorn coral observed during an initial coral health assessment in August of 2023 at Carysfort North, one of the seven Mission: Iconic Reefs in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. This coral was outside the survey area but documented as it was the only one that was not bleaching. Credit: Ben Edmonds/NOAA

In parallel with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, these processes take time and we need to be patient to see the results.

“The moment we, humanity, agrees to switch off everything that produces greenhouse gases and we don’t see results in a very short time period, we are going to be saying, ‘See? That wasn’t the solution.’ Because we as humans want results today. That is the instant gratification we are living today. And that is not a good approach.”

He is worried that knee-jerk reactions could transpire as extreme climate events continue to occur, and we will drop strategies that have been proven to work with time. This is a marathon, not a sprint.

“We are changing,” he says, in reference to the restoration community. “We are adapting to the new challenges to respond better. I think we are in a better situation now for whatever is coming.”