The Great Barrier Reef, located off the northeast tip of Australia, is one of the natural wonders of the world. In addition to providing vast ecological benefits, the Great Barrier Reef also is a tourist hotspot for Australia. It’s worth $5 billion annually and employs close to 70,000 people. And it has had a bad year. A long stretch of weeks with unusually warm waters, partly linked to El Niño, have led to heat stress and widespread bleaching across the 2,300-kilometer-length of the Great Barrier Reef.

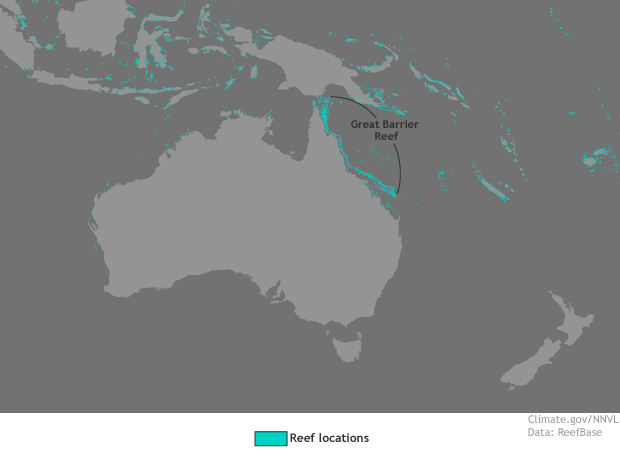

Location of the Great Barrier Reef off of northeastern Australia. Climate.gov image based on data from NOAA Environmental Visualization Lab.

Coral bleaching refers to the process where heat-stressed corals expel the colorful algae that usually live within their tissues. When water temperatures increase, though, the coral turns into an angry landlord, ejecting their beneficial tenants. After the loss of their beneficial algae, the corals turn completely white. The problem? Those tenants make almost all of the corals’ food. If the algae are expelled and do not return, the corals will starve and die.

Compared to healthy coral, which appear in shades of purple and gold, bleached coral on the Great Barrier Reef appear bone white. Photo by Mia Hoogenboom, for ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

The current bleaching event is being widely described as the worst ever recorded along the Great Barrier Reef. Based on updates from Australian scientists on April 20, 2016, 93% of the reefs surveyed showed at least some bleaching. Of 900 reefs that scientists observed during a flyover, only 68 had escaped bleaching. Between 60 to 100% of corals on 316 reefs were described as severely bleached, almost all in the north.

Historically, the northern reefs—the most remote—have been the most pristine and the least degraded, both by humans and by past bleaching events. During this event, 81% of reefs in the north had severely bleached. The central reefs were 33% severely bleached, while reefs in the southern section were only 1% severely bleached, with a quarter not bleached at all.

A compilation of aerial and underwater video showing bleaching on Australia's Great Barrier Reef in April 2016. Video provided by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Coral bleaching does not immediately kill corals. They do have the potential to recover if temperatures drop back below stressful levels and remain there for a long period of time—with no new shocks. This would allow surviving algae to reproduce and re-colonize the corals. But, as reported in the Washington Post, diving surveys of reefs in the north have shown close to 50% coral death already.

Coral stress does not just depend on how high water temperatures are, but also how long sea surface temperatures remain above average. Sea surface temperatures along the Reef since February have been 1-4°F (1-2°C) above average, exceeding 86°F across the most severely impacted areas in the north.

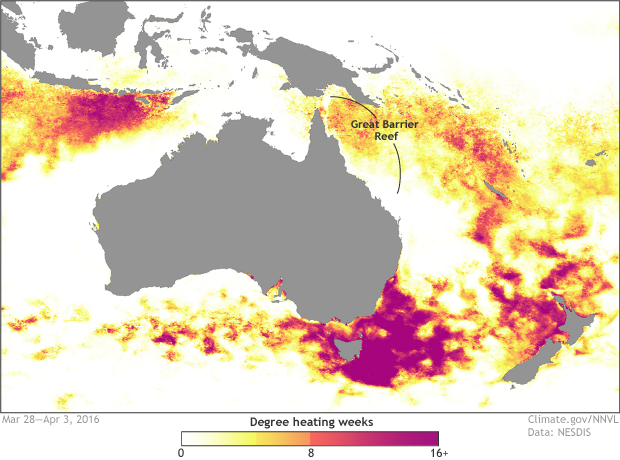

Accumulated weeks of heat stress for the waters surrounding Australia, including the Great Barrier Reef, during the week of March 28–April 3, 2016. Values larger than 4 (gold to orange) indicate that widespread coral bleaching is likely. Values above 8 (salmon to dark pink) indicate that significant bleaching and death is possible. During this period, elevated values of degree heating weeks are present across the northern section of the Great Barrier Reef, a historically pristine and unimpacted section of the reef. Severe bleaching across this region has taken place. Climate.gov image, based on imagery provided by provided by NOAA's Environmental Visualization Lab. Original data from NOAA's Coral Reef Watch project.

One way NOAA scientists track the buildup of coral heat stress is with satellite maps of degree heating weeks. During the week spanning the end of March and beginning of April, degree heating week values were high, showing long-lasting heat stress across the central and northern sectors of the reef. This is consistent with where the most severely bleached reefs were found.

The warmth associated with El Niño (the warm phase of a natural climate pattern that swings back and forth in the tropical Pacific) was a major contributor to this record-breaking bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef, but long-term warming trend in the oceans worldwide due to human-caused climate change is the underlying cause.

Stay tuned for a follow-up post in the next week or two that explores this event in more detail and talks about the future of the Great Barrier Reef in the face of continued global warming.