Late in 2015, we published a series of stories about a large-scale harmful algal bloom year off the West Coast that resulted in numerous marine animal deaths and closures of recreational and commercial fisheries in California, Oregon, and Washington. At the time, scientists hypothesized that the severe, widespread toxic bloom was connected to unusually persistent warmth in the waters of the North Pacific, but actual evidence was limited.

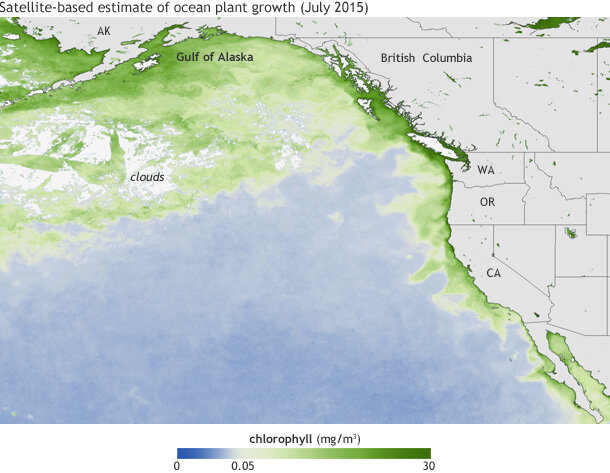

Average chlorophyll concentrations (milligrams per cubic meter of water) in July 2015. The darkest green areas have the highest surface chlorophyll concentrations and the largest amounts of phytoplankton—including both toxic and harmless species. NOAA Climate.gov map based on Suomi NPP satellite data provided by NOAA View.

New research led by Oregon State University and NOAA scientists supports the connection. The scientists have linked basin-wide warmth across the Pacific Ocean to the presence of elevated levels of a natural toxin—domoic acid—in razor clams in Oregon waters. According to the study, warmer oceans led to a higher likelihood that toxins would surpass safe threshold levels in Oregon, Washington, and California.

What’s new about this research?

While records of the temperature and large-scale circulation of the tropical and North Pacific Ocean date back decades, long-term records of harmful algal blooms along the West Coast are much shorter in length. The first observation of domoic acid in shellfish along the West Coast was recorded in 1991 in Monterey Bay, California, after sea lions and sea birds were observed having seizures after eating sardines and anchovies laced with the toxin. Thanks to monitoring efforts along the U.S. West coast that started in the early 90s, scientists now have a long enough record to correlate the most problematic harmful algal bloom events to oceanic and climatic factors which are measured over long time scales.

And what did they find?

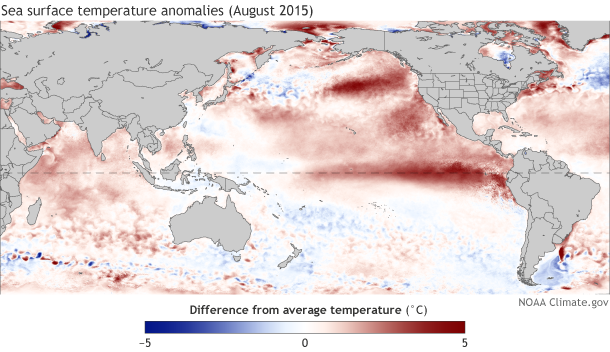

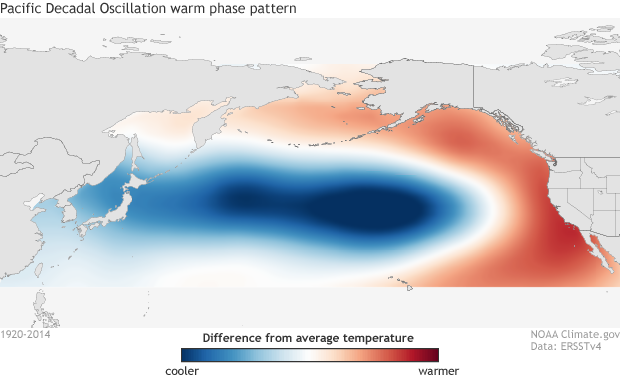

Events with high levels of domoic acid in shellfish tend to be associated with or immediately follow warmer-than-average ocean conditions in the tropical and North Pacific Ocean. Case in point: the large area of above-average temperatures that was dubbed “the Blob,” which extended along the West Coast in 2015. Similarly, shellfish poisoning events often occurred during warm phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO).

Sea surface temperatures during August compared to the 1981-2010 average. Climate.gov figure, based on data from NOAA View.

The warm phrase of ENSO—El Niño—brings above-average water temperatures to the eastern and central tropical Pacific. Warm phases of the PDO mean warmer than average ocean temperatures along the West Coast up to and extending past the Gulf of Alaska. (Head to the ENSO blog for a more in depth explanation of ENSO and the PDO.)

Sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly pattern associated with the positive (or warm) phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). Red shading indicates where SSTs are above average, and blue shading shows where SSTs are below average. During negative (cold) phases, the pattern reverses. Image adapted by NOAA Climate.gov from original by Matt Newman based on NOAA ERSSTv4 data.

Having found a strong link between warm conditions and toxic domoic acid events in Oregon, the team used the relationship they found to construct a risk assessment model for domoic acid poisoning events along the West Coast from Washington to California. The model predicts the timing and location of events where domoic acid in shellfish could exceed safe thresholds. The scientist’s goal was to produce a model that can be used and interpreted by scientists and nonscientists-alike so decision makers could have advanced warning of damaging events.

Why is this research important right now?

The research comes at a critical time. The 2015 bloom of algae, unprecedented in scope, had widespread impacts for marine and shellfish fisheries up and down the West Coast of the United States. Levels of the domoic acid were high enough to close recreational razor clam harvest in Oregon and Washington and a large portion of Washington’s Dungeness crab fisheries. In California, the California Fish and Game Commission had to close the year-round rock crab fishery north of the Ventura-Santa Barbara county line and had to delay the state’s opening of the recreational and commercial Dungeness crab fishery.

Dungeness crab ready to eat at Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco, on March 26, 2005. Photo by Jon Sullivan, via Wikimedia Commons.

Closures to parts of the Dungeness crab fishery extended north to Washington’s Puget Sound. In total, closures of the Dungeness crab fisheries along the West Coast due to high levels of DA resulted in a $100 million decrease in value according to the Fisheries of the US Report 2015.

In addition to substantial negative economic impacts, toxic events can lead to the mass death of marine mammals and can pose potential public health issues for humans. Human consumption of shellfish with high levels of domoic acid can cause a neurological disorder called Domoic Acid Poisoning or Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning.

Red Tide caused by Dinoflagellates off the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Pier, La Jolla California. Photo by P. Alejandro Díaz and Ginny Velasquez, via Wikipedia.

Early warning of toxic algal events could allow decision makers to take preventive measures to avoid costly hits to the economy—fishermen having to discard a contaminated catch, for example—and dangerous public health impacts. The model may be especially helpful as warmer ocean conditions become more persistent as a result of global warming, posing a risk of more frequent domoic acid closures along the West Coast.

References

McKibben, S. M., Peterson, W., Wood, A. M., Trainer, V. L., Hunter, M., & White, A. E. (2017). Climatic regulation of the neurotoxin domoic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(2), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606798114