Strip of cool water lingering in tropical Pacific in July 2016

Details

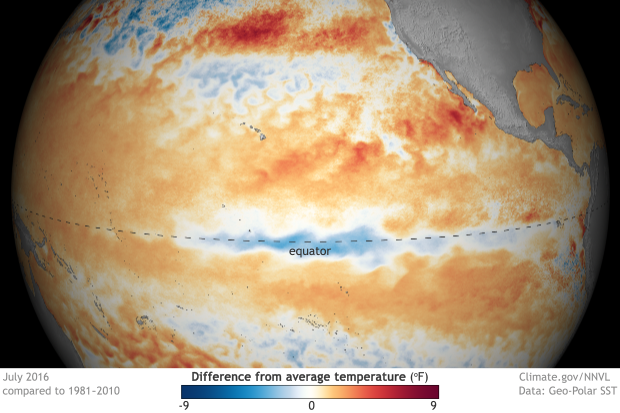

Compared to conditions in June 2016, a slightly wavy strip of cooler-than-average water along the equator in the central to eastern Pacific appeared to have expanded just a little and cooled off a bit further in July. A persistent cool spot in that area is one of the criteria that climate experts use to monitor and predict La Niña—the cool phase of the ENSO climate pattern.

The map at right shows where surface temperatures of the Pacific Ocean in July 2016 were cooler (blue) or warmer (orange and red) than the 1981-2010 average. The darker the color, the larger the temperature departure.

Climate experts keep a close eye on the tropical Pacific Ocean because it is at the heart of ENSO. Short for El Niño-Southern Oscillation, ENSO is a powerful natural climate pattern in which the central/eastern tropical Pacific swings back and forth between a warm and rainy state (El Niño) and a cooler and drier state (La Niña).

El Niño and La Niña disrupt wind, air pressure, and rainfall patterns throughout the tropics. The disruptions can have side effects on global climate, including shifting the location of the mid-latitude jet streams that guide storms towards the United States.

Earlier this year, one of the strongest El Niño events on record drew to a close, and temperatures in the tropical Pacific have steadily cooled off. Now, climate experts are keeping an eye on that cool spot and have issued a La Niña watch. The next El Niño/La Niña forecast discussion will be issued tomorrow morning. Emily Becker will be recapping the high points for us on the Climate.gov ENSO Blog.

About these data

This image of sea surface temperature departures is from a dataset that combines in situ (“on site”) measurements, like those recorded by buoys, and near-real-time satellite observations. Using both sources generates high resolution images that show fine-scale details in our oceans.

These daily, high-resolution sea surface temperature data provide a detailed first glance at ocean conditions during an evolving El Niño or La Niña, which can then be used to help “start up” (or in scientist-speak, initialize) forecast models. Because they are more detailed, they also make more interesting images.

However, our experts caution, if your goal is to compare the relative strength of El Niño events over time, these maps are not your best option. Just like two scales may not give you the exact same weight, satellite-based datasets from different eras (different missions) can have subtle differences, not all of which can be accounted for—at least not with the precision required for comparing events that may only differ from one another by just a few tenths of a degree.

For historical comparisons, you need datasets that have been purposefully pieced together into a seamless, long-term record specifically for that purpose.

For more El Niño updates, please follow the Climate.gov ENSO Blog or read the latest monthly El Niño advisory update, which is issued the second Thursday of every month from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center.