Understanding COP

I am seeing news stories about “COP.” What is COP?

COP is an international climate meeting held each year by the United Nations. COP is short for “Conference of the Parties,” meaning those countries who joined—are “party to,” in legal terms—the international treaty called the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Parties to the treaty have committed to take voluntary actions to prevent “dangerous anthropogenic [human induced] interference with the climate system."

Countries take turns hosting an annual meeting at which government representatives report on progress, set intermediate goals, make agreements to share scientific and technological advances of global benefit, and negotiate policy.

What is “dangerous” interference with the climate?

The idea of what is a dangerous amount of global warming is partly a scientific question (what impacts are likely to occur with a given amount of warming) and partly a value judgement (how tolerable those impacts would be). Countries recognized that as warming increased, the risk of impacts that most would consider intolerable would also increase. Based on the science that was available when the UNFCCC treaty was negotiated in 1992, parties agreed that 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures was ‘an upper limit beyond which the risks of grave damage to ecosystems, and of non-linear responses, are expected to increase rapidly.’

What is the Paris Agreement?

More than three decades have passed since the original UNFCCC treaty was developed. Research over that time shows that for some countries and vulnerable ecosystems, the risk of grave damage rapidly increases with less than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming. To account for this, most of the parties to the original UNFCCC treaty signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2015, which obligated countries to develop additional voluntary reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that would limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees F), and preferably to no more than 1.5 Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

How do these climate treaties work?

The parties agree to specific goals for limiting human emissions of greenhouse gases (including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and halogen-containing gases like CFCs) to a specific amount by a given year in the future. Countries participating in the treaty develop their own voluntary pledges—known as Nationally Determined Contributions—to meet the agreed-on targets. Countries are free to develop a mixture of policies that is most economical or advantageous for them. They must report on their successes or failures to meet their voluntary targets at the annual COP meetings.

Solar field at the Agahozo Shalom Youth Village in Rwanda east of Kigali. It is the first utility-scale, grid-connected, commercial solar field in East Africa. Photo by Sameer Halai, USAID/Power Africa, from the GPA Photo Archive. Used under a Creative Commons license.

Where do we stand?

Climate simulations show that to limit warming to 1.5°C, with no overshoot, global carbon dioxide emissions from human sources must decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, and reach net zero human emissions around 2050. To limit global warming to below 2°C, models indicate we need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by about 25% over 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero around 2070.

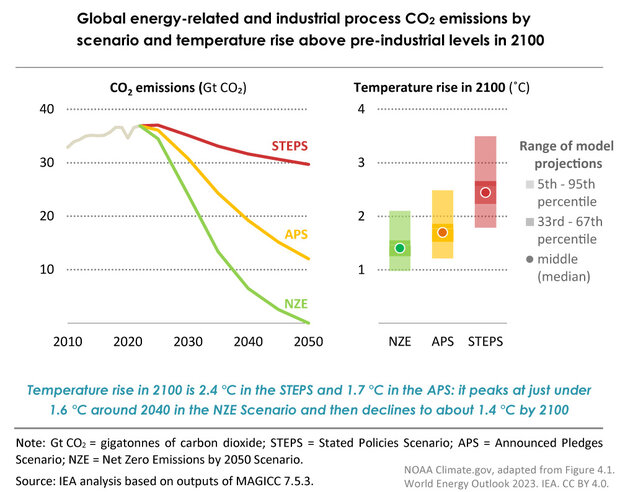

According to the International Energy Administration’s 2023 World Energy Outlook (see page 91), if all the pledges that individual countries have announced so far are implemented fully and on time, Earth’s temperature is likely to rise by about 1.7 degrees Celsius (3.1 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100. That’s under the “dangerous” 2 degrees Celsius threshold, and it keeps the goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius within reach.

On the other hand, when the International Energy Administration considered only the policies that are already in place or under development, they projected that warming will likely reach about 2.4 degrees Celsius (4.3 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100. The difference means that there is a gap between what countries have pledged and what they have been able to put into practice at this point.

(left) Based on countries' stated climate and energy policies to date, global emissions will fall only from about 36 billion metric tons per year to about 30 (red line). But if all countries follow through on their announced pledges (yellow), emissions will drop to around 12 billion metric tons, which is much closer to the goal of net zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 (green)—needed to keep global average warming to no more than 1.5 ˚C above pre-industrial temperature. (right) Median (middle of the model range) warming by 2100 if we reach net zero by 2050 is projected to be around 1.4 ˚C (2.5 ˚F) (green dot). If all countries meet their pledges, median warming is projected to be 1.7 ˚C (3 ˚F). Actual policies to date are projected to lead to 2.4 ˚C (4.3 ˚F) (red dot). NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from Figure 4.1 in World Energy Outlook 2023 by the International Energy Administration. Used under a Creative Commons license.

What pledges has the United States made as part of the Paris Agreement?

To learn more about the current Administration’s climate strategies, policies, and opportunities, visit the White House Climate Task Force website.