It’s that time of the year again. When the weather outside gets frightful but the fire is so delightful… or something like that. No, I’m not talking about the Holiday season. I’m talking about lake effect snow season!

Satellite image of the Great Lakes taken during a "lake effect snow" event on December 14, 2016. Parallel rows of clouds streak across the lakes in the direction of the wind. Downwind of the lakes, especially Erie and Ontario, the cloud streaks thicken into strong snow bands. NASA/NOAA image from the Suomi-NPP Satellite provided by the NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory.

A winter wonderland

Two separate lake effect snow events across the Great Lakes buried parts of northern New England and the upper Midwest under feet of snow during the beginning and middle of December. From December 8-11, frigid westerly winds carrying air from the Canadian Arctic passed over the relatively warm Great Lakes (~45°F), setting the stage for a multi-day lake effect snow event.

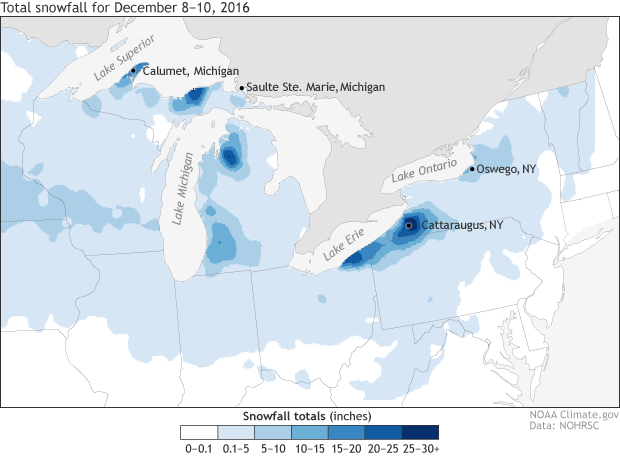

In upstate New York, areas downwind of Lake Erie received up to three feet of snow in 72 hours. Cattaraugus observed 36 inches of snow over 72 hours. East Concord topped that with 37.8 inches. Meanwhile, a strong lake effect snow band off of Lake Ontario dropped almost two feet of snow in far northern New York. Highmarket received 17.9 inches of snow. Oswego recorded 15.8 inches.

In Lower Michigan, blinding lake effect snow caused deadly car accidents on I-96 while in Upper Michigan two feet of snow was recorded from December 6-10 near Barker Creek. Calumet, Michigan on the Upper Peninsula observed 18 inches of snow. One to two feet of snow was also measured in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin off the Great Lakes.

Observed snowfall analysis from December 8 through December 10, 2016. Lake effect snows off of many of the Great Lakes during the time period dropped feet of snow. Climate.gov image using data provided by the National Operational Hydrologic Remote Sensing Center.

A week later another shot of cold air over the Lakes set off the Lake Effect snow machine again. On December 14-15, extremely heavy snow fell across Michigan, Upstate New York, and Ohio. Sault Ste. Marie in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan found themselves with 11 inches of new snow on December 15. In Cleveland, snow fell at rates of up to 1-2 inches per hour on December 15. Meanwhile in central New York, snow fell fast enough to produce white out conditions and thundersnow in Oswego. Winds even gusted to 84mph during the strongest lake effect snowstorm in Oswego. Around 20 inches of snow was recorded close to Redfield, New York, downwind of Lake Ontario.

Why does this happen around the Great Lakes?

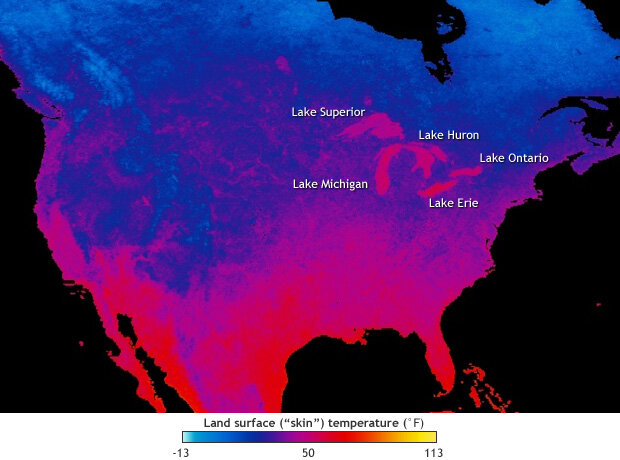

Lake effect snow is a common occurrence for areas downwind of the Great Lakes. It is the result of cold, arctic air flowing over the still relatively warm—and ice free—waters of the Great Lakes. (The temperature of the lake waters during the events were between 40-50°F.) As the air moves over the lakes, it warms and becomes moister. Air that is warmer than its surroundings will rise. It’s why you hop into a hot air balloon and not a cold air balloon—unless you like your balloon rides to take place on the ground.

November 2016 nighttime land surface temperature, based on NASA satellite data. The land surface cools off in the fall and early winter faster than the Great Lakes. Image courtesy NEO project.

How much the air rises depends on the difference between the temperature of the lakes and the air above it. The larger the difference, the more unstable the atmosphere will be, the more energetically the air will rise, and the higher the potential for lake effect snow.

Once this rising air reaches the shores downwind of the Great Lakes, friction increases, and the winds slow down. The slower-moving air creates an atmospheric ramp. Faster-moving air over the lake (where friction is lower) overtakes the slower moving air over land and runs overtop of it, increasing the upward motion and leading to potentially heavier snowfall. It’s like sliding on ice on a sidewalk. The low friction means you can glide quickly. However, once the ice ends and the concrete begins, the high friction of the concrete stops your forward motion, and you go flying…gracefully of course. This procedure can cause significantly heavy bands of snow where snowfall amounts could reach multiple inches per hour, reducing visibility to near zero.

Conditions for lake effect snow off the Great Lakes are often met after the passages of strong cold fronts, as arctic air rushes down out of Canada and over the Great Lakes. The lake effect snow season ends by late winter as the lakes begin to freeze over, drastically reducing a couple of the ingredients—moisture and relative warmth—needed to kick start the snow machine. But until that time, don’t be surprised to hear about more lake effect snow in the news.