Can NOAA predict the next flood? New research shows promise

Heavy rain and flooding on April 12-13, 2023, caused Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport to shut down for about forty hours. Credit: Joe Cavaretta/South Florida Sun Sentinel. Used with permission.

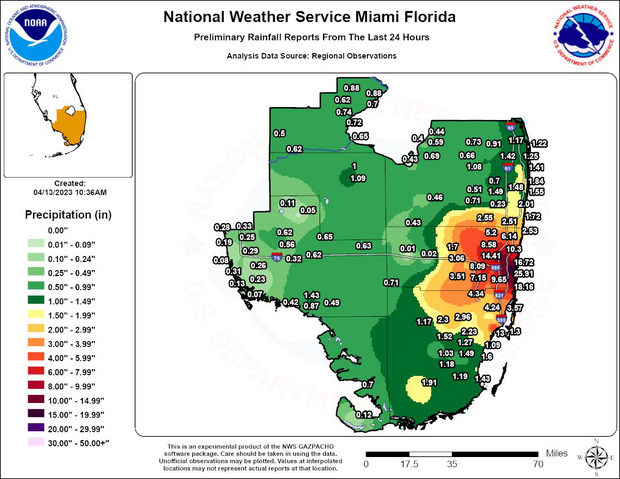

April 12, 2023, was a day Jennifer Jurado, Chief Resilience Officer for Broward County, Florida, will never forget. What began as a routine day of meetings turned into a struggle for survival as an unexpected 1,000-year rainstorm deluged the county, dropping nearly 26 inches of water in just 24 hours.

A map showing preliminary rainfall totals for 1,000-year rain event in South Florida from April 12-13, 2023. A total of more than 25 inches (dark purple) was observed right on the coast. Map by NOAA National Weather Service.

At 1PM that day, Jurado convened a meeting in Ft. Lauderdale to discuss a resilience plan years in the making. She noticed that a rainstorm had begun. The meeting ended at 4PM, and Jurado departed shortly thereafter for Ft. Lauderdale airport for a business trip. She expected a 30-minute drive.

Jurado never made it to the airport, which closed due to the storm. It took her an hour to travel one mile through floodwaters. “I found myself locked in the area of worst flooding, between my building in downtown Ft. Lauderdale and the airport,” said Jurado. “There’s a sense of being trapped and having no line of sight as to how to navigate. Like in a labyrinth, all you can see is what’s in front of you.”

When the sun began to set, it became difficult for Jurado to judge water depth and distinguish between soaked roadways, coastal waterways, and canals. The South Florida Water Management District and other authorities manage about 1,800 miles of canals in Broward County, and the waterways present a hazard under dark, rainy driving conditions. “People do drive into canals, and occasionally we hear of drowning deaths,” said Jurado. Broward’s primary canals are generally about 15 feet deep and 100 feet across.

Aerial view of part of the massive canal system in Broward County, Florida. Photo by Jennifer Jurado.

After three hours of slow motion, Jurado made it to Interstate 95 and took the off ramp towards her home. She eventually got home to her family but lost her car to the rising waters; her car engine flooded on the off ramp.

The event confirmed the worst-case rainfall scenarios that Jurado and her team were studying. Similar major rainstorms, not associated with hurricanes or tropical storms, occurred again in Broward County in August and December 2024, reinforcing the relevance of their work.

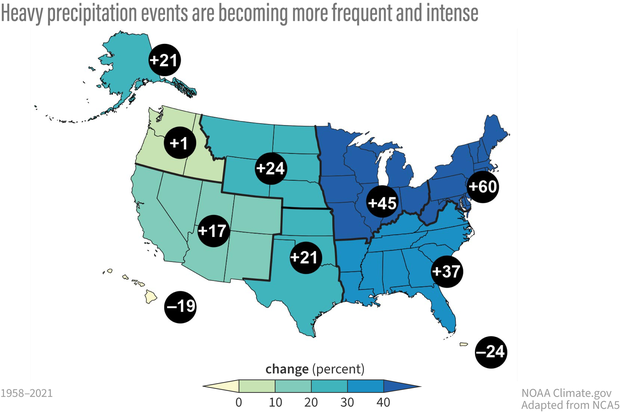

Extremely heavy rainfall is increasing across the United states. This map shows observed percent changes in total precipitation falling on the heaviest 1% of rainy days from 1958–2021. Numbers in black circles depict percent changes at the regional level. Data were not available for the US-Affiliated Pacific Islands and the US Virgin Islands. Image adapted from original in the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Jurado isn’t alone in facing these challenges. According to the Fifth National Climate Assessment (NCA), heavy precipitation in the contiguous United States has increased since the 1950s. The Southeast has seen a 37 percent rise in total precipitation on the heaviest 1 percent of days; the Northeast has seen a 60 percent rise from 1958-2021. The NCA also notes that “extreme precipitation–producing weather systems ranging from tropical cyclones to atmospheric rivers are very likely to produce heavier precipitation at higher global warming levels. Recent increases in the frequency, severity, and amount of extreme precipitation are expected to continue across the US even if global warming is limited to Paris Agreement targets.”

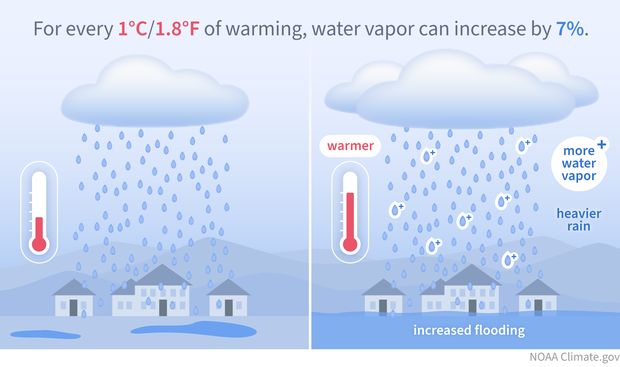

On average, for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) the atmosphere warms, it can hold 7 percent more water vapor. When atmospheric processes do trigger rain, that extra "background" water vapor can make it rain more heavily, leading to increased flooding. NOAA Climate.gov illustration.

NOAA Climate Program Office research on extreme rainstorms

NOAA, the federal science agency responsible for weather forecasting and climate modeling, helps resilience officers like Jurado, and other local government officials, to better understand and prepare for extreme rainfall.

For her resilience work, Jurado uses several NOAA products: sea level rise projections, Physical Oceanographic Real-Time System monitoring system, the ATLAS 14 precipitation statistics, and daily tide predictions. “Our whole emphasis at Broward County is on early and smart investment to avoid losses, damages, exposures, and disruptions. This philosophy protects our people, infrastructure, and economy. But we can’t do our jobs without the NOAA data,” she said.

For more than thirty years, the NOAA Climate Program Office has invested in top researchers to advance climate science and services, addressing foundational questions and supporting resilience planning. The office explores climate phenomena like El Niño, mapping their processes in fine detail. Funded scientists provide essential observations and data that drive scientific discovery.

Predicting extreme rainstorms like Jurado’s is a major scientific challenge. These storms form in a matter of hours, driven by complex moisture, temperature, and wind patterns. To provide the best public service, NOAA’s National Weather Service would like to predict major precipitation events weeks, months, and even years in advance. Lives, livelihoods, property, and critical infrastructure are at risk, and NOAA scientists have pursued the science of precipitation prediction for decades.

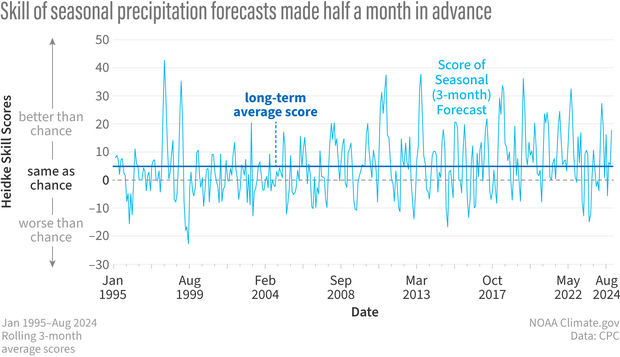

To unlock the secrets of long-term precipitation prediction, the Climate Program Office studies key patterns and processes in the formation of extreme rainstorms. Over time, with enough of these insights, scientists could build more accurate computer models and long-term forecasts. NOAA calls this relationship between research and forecasting the “research-to-operations pipeline,” and it is critical to their public service mission.

Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge

Given the massive scope of precipitation research, the Climate Program Office is working with partners at the national and international level. Nationally, the group is partnering with other programs and centers in NOAA, such as the Weather Program Office and the Weather Prediction Center, on the Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge. Internationally, the office is partnering with other U.S. agencies and other countries in the World Meteorological Organization for the Global Precipitation Experiment.

Launched in 2020, the Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge aspires to increase the rate of improvement of NOAA precipitation forecast accuracy across time scales from daily to decades. It will help U.S. communities prepare for extreme rain, floods, and droughts.

The skill of seasonal (rolling 3-month average) precipitation forecasts (bright blue line) is often significantly better than statistics say we could expect due to chance (indicated by a Heidke skill score above 0, which is shown by the dashed line). But on average (dark blue line), skill has remained relatively modest for several decades. The Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge aims to speed up the pace of improvements. Climate.gov graph, adapted from Climate Prediction Center data.

Progress depends on partnerships

The Climate Program Office’s research enterprise succeeds on the strength of its many partnerships. University of Miami climate scientist Ben Kirtman is one of many key investigators funded by the office’s Earth system division. Kirtman’s research group has been progressing in precipitation prediction research, contributing to the Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge. In October 2022, Kirtman and colleagues published a paper in Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems summarizing their investigation into the factors that could help predict rainfall patterns in the Southeastern U.S.

“There’s a gap in our ability to predict summer rainfall in this region,” said Kirtman. “We want to understand why. This kind of rain is one of the hardest to predict, and climate change is making the problem even more complex.”

With the help of machine learning, Kirtman and his colleagues found promising sources of predictability in the climate system. “Our research shows that there are large-scale circulation patterns associated with both winter and summer rainfall extremes, and important North Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies [temperatures that are warmer or cooler than normal] associated with Gulf Stream variability that are a potential source of predictability,” explained Kirtman.

The future of precipitation research

Among the Climate Program Office’s priorities for future precipitation research is the upcoming Tropical Pacific Observing System Equatorial Pacific Experiment (TEPEX) field campaign (2026-2028). The field campaign is designed to investigate how ocean-atmosphere interactions in the tropical Pacific affect weather patterns around the world, including extreme precipitation events in the United States.

“Through collaborative efforts with NOAA partners and the international research community, we have begun to address these challenges by advancing datasets, refining models, and deepening our understanding of climate system interactions,” said Jin Huang, Division Chief for the Climate Program Office’s Earth System Science and Modeling division.

With the office’s support, Ben Kirtman’s research group continues to search for sources of precipitation predictability. “We are developing models that will help us assess the chances that the extreme rainfall event that happened in Ft. Lauderdale in April 2023 will happen again,” he said.

Looking ahead, Jennifer Jurado remains hopeful, but she knows the future of resilience planning relies heavily on NOAA’s continued advancements in precipitation prediction. One of the unique dilemmas posed by extreme rainfall in Broward is canal water management. Thanks to NOAA’s National Hurricane Center, Broward has advanced notice of several days before tropical storms and hurricanes, allowing them time to lower their canal water to make room for the rainfall. High-intensity, short duration cloudbursts, however, strike with little notice, leaving no time to adjust the canals.

“We would like to have the strength of NOAA’s predictions for these future rainfall trends,” said Jurado. “NOAA’s front-end investments are key. When investments come after local impacts and losses, they are too late. Targeted, early investment is the foundation of community resilience.”

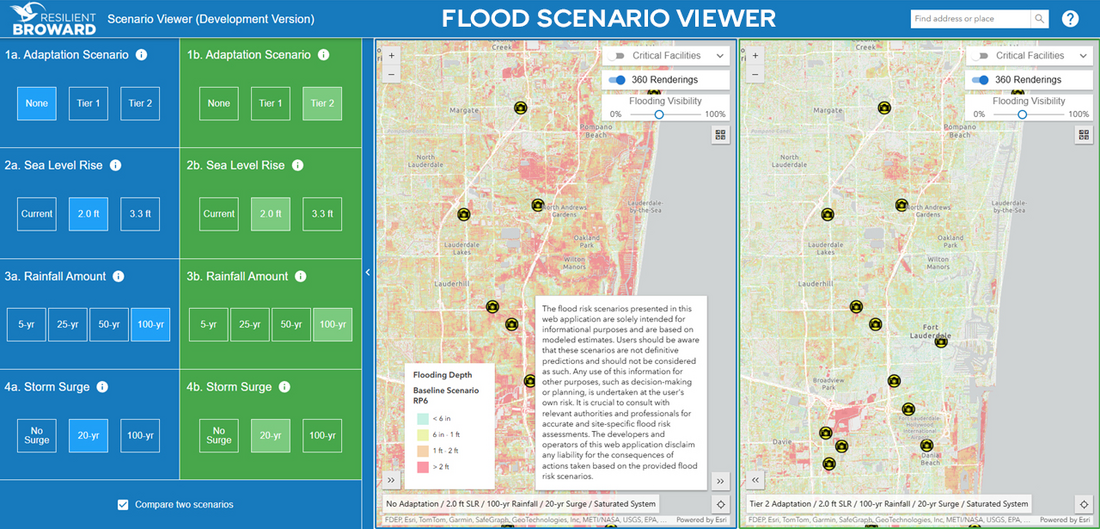

Jennifer Jurado and her team in Broward County have built a Resilience Plan Dashboard, rich with maps and data, to aid their planning for flooding. Credit: Jennifer Jurado

For Jurado, the flood that forced her to abandon her car on the roadway was a wake up call—not just for Broward County, but for every U.S. community facing the growing threat of extreme rainstorms.

Sources & references

- Interview with Jennifer Jurado, February 7, 2025

- Interview with Ben Kirtman January 2, 2025

- Interview with Jennifer Jurado, January 7, 2025

- https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/aies/1/4/AIES-D-22-0011.1.xml

- https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/fort-lauderdale-got-25-inches-rain-unprecedented-storm-rcna79657

- https://www.noaa.gov/explainers/precipitation-prediction-grand-challenge-strategy

- https://www.wusf.org/weather/2023-04-21/nightmare-flooding-fort-lauderdale-frustration-homelessness

- https://wsvn.com/news/local/broward/fort-lauderdale-remembers-historic-2023-floods-that-overtook-city-broward-house-reopens/

- https://www.cnbc.com/2023/04/14/photos-show-flooding-in-fort-lauderdale-other-parts-of-south-florida.html

- https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/12/weather/florida-flash-flood-fort-lauderdale/index.html

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/analysis-fort-lauderdales-historic-flooding-is-a-sign-of-things-to-come-heres-who-is-at-risk-and-how-to-prepare

- https://climatecenter.fsu.edu/products-services/summaries?view=article&id=629

- https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/2/

- https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/

- https://cpo.noaa.gov/about-cpo/our-strategic-plan/

- https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2023-historic-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters

- https://www.noaa.gov/explainers/precipitation-prediction-grand-challenge-strategy