January 2022 La Niña update: family game night

Happy new year! This La Niña event is likely near peak strength as we start 2022. Related impacts to global weather and climate will continue through the rest of winter and into the spring, however, because climate impacts lag tropical Pacific sea surface temperature changes. Forecasters favor a transition to neutral in the April–June period.

Chutes and Ladders

The sea surface temperature in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific—our primary measurement of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) system—was 1.1° C cooler than the 1991–2020 average in December, via the ERSSTv5 observation dataset.

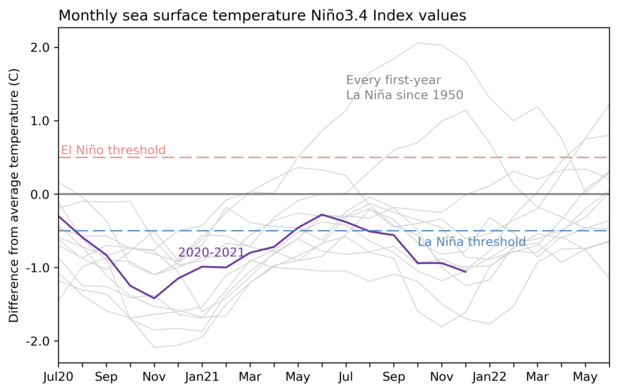

Monthly sea surface temperature anomalies (difference from average) in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific for 2020-21 (purple line) and all other years (gray lines) starting from first-year La Niña winters since 1950. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv5 temperature data.

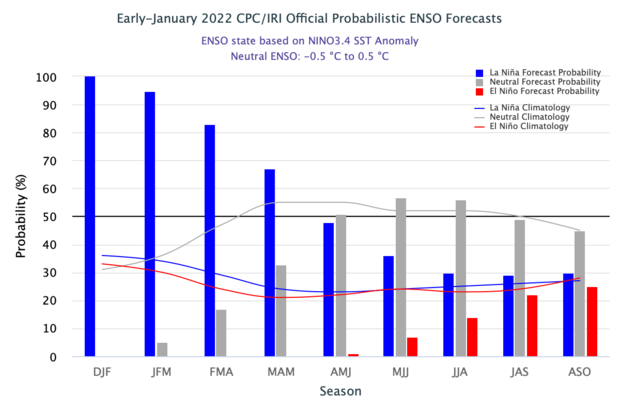

The three-month temperature deviation from average in Niño-3.4, the Oceanic Niño Index, for October–December was -1.0° C. This marks the fourth three-month period (“season” in climate prediction parlance) in a row with an index more than 0.5° C cooler than the long-term average. It takes five seasons in a row to qualify as an official El Niño or La Niña event and get colored red or blue in the historical events table. It’s certain that this event will qualify—forecasters give the December–February period a 100% chance of being in La Niña territory, and 95% likelihood for January–March.

The official CPC/IRI ENSO probability forecast. The bars show the seasonal chances for each possible ENSO state—El Niño (red), La Niña (blue), and neutral (gray) from winter 2022 through fall 2022. The forecast is based on a consensus of CPC and IRI forecasters, and it is updated during the first half of the month, in association with the official CPC/IRI ENSO Diagnostic Discussion. It is based on observational and predictive information from early in the month and from the previous month. Image from IRI.

Why five seasons? Because, when they needed come up with an official ENSO definition, an international committee of ENSO experts argued that we need equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies to persist for this duration in order to ensure that the atmosphere and ocean in the ENSO system are truly coupled (supported by a variety of atmospheric and ocean indexes). A persistent, coupled tropical Pacific also makes it more likely that ENSO can modify global weather and climate patterns too.

Atmospheric conditions in the tropical Pacific region also reflected La Niña in December, with evidence of a strengthened Walker circulation. La Niña’s cooler-than-average central/eastern equatorial Pacific enhances the normal warm-west/cool-east temperature gradient, so the atmospheric response is an enhanced version of the normal circulation pattern. This means more rising air and clouds in the west, stronger west-to-east upper-level winds, drier conditions in the central Pacific, and stronger trade winds near the surface, all of which were clocked during December. The links here lead to the International Research Institute for Climate and Society’s Maproom, where you can select the month and the level in the atmosphere.

The Game of Life

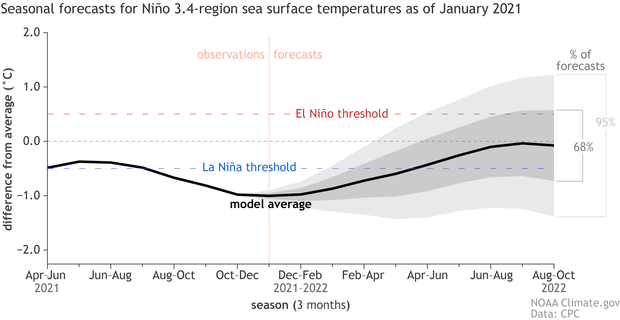

So La Niña will stick around for the next few months, but what about next summer/fall? Even though we would really like to know, especially given ENSO’s effect on tropical storms, this is still really unclear. As I discussed last month, a third-year La Niña, neutral, or El Niño are all still on the table. Computer models, including those from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble, show a broad range of potential outcomes for the fall, too.

Climate model forecasts for the Niño-3.4 temperature anomalies in 2022. Average dynamical model data (black line) from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME): darker gray envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter gray shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA Climate.gov image from University of Miami data.

We’ll have to play a few more rounds to get a clearer picture of how the tropical Pacific will set up for later this year.

Trivial Pursuit

This La Niña’s effect on rain and snow patterns in North America has been pretty typical so far, with drier conditions through the south-central and southeastern U.S. and wetter over the Pacific Northwest, northern California, and the Ohio Valley over the past three months. The excess precipitation in Washington State has been in the news lately, making me curious about how this year fit into the historical context. More precipitation in the Pacific Northwest, especially more snow, is one of the more consistent La Niña impacts, as the jet stream tends to get deflected northward, bringing more storms with it.

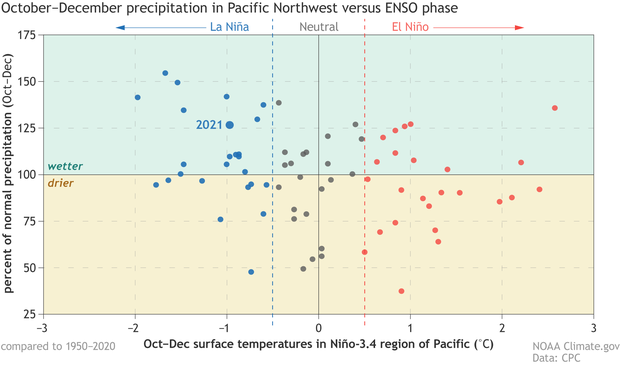

Dots show October–December precipitation in the Pacific Northwest for every year from 1950–2021, sorted by ENSO phase. The vertical axis shows the percentage of accumulated October–December precipitation relative to the 1950–2020 average. The horizontal axis shows the October–November Niño 3.4 Index, with blue dots indicating forecasts of La Niña conditions (Niño 3.4 Index less than -0.5°C), black dots indicating neutral ENSO forecasts (Niño 3.4 Index greater than -0.5°C but less than 0.5°C), and red dots indicating forecasts of El Niño conditions (Niño 3.4 Index greater than 0.5°C). In the upper left part of the graphic, you can see that the region's wettest years occurred during La Niña. Region averaged over all land gridpoints, 45°N–50°N, 120°W–125°W. Data from the Climate Prediction Center’s Unified Raingauge dataset and ERSSTv5. Figure by climate.gov.

Winters with more precipitation (I’m combining rain and snow here, with snow measured as rain-equivalent) tend to occur during La Niña, and drier winters during El Niño, although of course there are exceptions! La Niña 2021–22, a borderline moderate event so far, fits the pattern, with about 125% of average precipitation in October–December. The Pacific Northwest also has a climate-change related trend toward wetter conditions in the fall and winter. You can look at the trend and La Niña impacts side-by-side here.

Yahtzee

Speaking of the jet stream, stay tuned to the ENSO Blog for a special guest post on this topic later this month! And, of course, your trusty regular correspondents will be here to keep you updated on the forecast and all things ENSO.

Comments

Next season way too early

Our December weather in California was actually un Nina like with record December snowfall in areas where it was not supposed to be. During a La Nina year we would expect the bulk of the snow and rain to hit the northern half of the state. But we've experienced record snowfall in the central and southern sierras with high rainfall amounts in areas of Southern CA. My concern is this dry persistent January spell statewide and what February and march are going to look like which will diminish our great December and keep us in a severe drought. I hope the ECMWF plots are accurate and we end up in an El Nino next year. I would rather put my weather rain chances with that ENSO state. i know what the seasonal models for the remaining winter is. What are your thoughts?

At this point, these's no…

At this point, these's no indication that the pattern will revert back to the early winter one. CPC will issue a first look at February and an update to the February-March-April outlook on Thursday, so you'll get an idea as to what we are thinking then. Also remember that the outlooks are issued in terms of probabilities, with the most likely solution indicated on the maps. However, less likely solutions do occur as we've seen in the past.

Weather

Here in coastal Georgia La Nina has brought cold and dry weather since early January especially at night. I am ready for an El Nino with more clouds and higher nighttime temps. Tired of seeing my flowers get zapped in January by frosty nights.

Southeast

January definitely saw a big swing in temperatures for the southeastern US. Check out Emily's latest post for more details.

la Ninas

Hi Emily,

I hope you have a time for a second La Nina question. The last several years we have experienced far more La Ninas than El Ninos. We've had four la ninas since 2016 and one El Nino. Is there anything contributing to this?

Historically, there does…

Historically, there does appear to be some level of multi-decadal variability in the frequency of El Nino and La Nina episodes. Hard to say that what we've seen lately is anything but that. There's been no research that implies climate change has had an impact on the frequency of either El Nino or La Nina.

Ecuador

The El Niño 2022 - 2023????

Too early too tell what next…

Too early too tell what next year will look like. Right now model plots are pointing to an ENSO neutral year although model accuracy right now for next fall and winter is quite low. We have to pass the spring predictability barrier. After May the picture will start to become clearer

Thank you Mr. Halpert

For your responses. I really hope we are done with La Ninas for awhile. I would rather try a significant El Nino for a change

Third La Nina Still possible 2022-2023

just wondering i wouldnt rule out a Third La Nina they are not as common as back to back La ninas but they do happen the 1950s 1954-1957 1970s 1973-1975 it happened and was followed with a major El nino and again 1998-2000 we are actually due for another tripple La nina

Ill bet against that one

I'd put my money on an El Nino over a La Nina next year. Sorry east coast

E-Nino

Thanks for the updates . what are chances we would bounce to strong El-Nino next winter season . i realize it is too early to say but did it happen in the past ?

Thanks

Mohamed

Jordan

The chances we go into an El…

The chances we go into an El Nino coming up are shown in this plot:

https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/?enso_tab=enso-cpc_plume

This is updated every month (2nd Thursday of the month) in association with the ENSO discussion which you can find here:

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.shtml

Thank you

Thank you so much statistically significantly !

THE NIÑO 2022 to 2023?

THE NIÑO 2022 to 2023?

See the links above which…

See the links above which will update once a month (and the forecast horizon will continue to extend out).

Heat in the Indian Ocean

First, let me say how much I really appreciate all of you for putting so much information into this blog every month! Thank you!

I've been looking at the MJO forecasts, it looks like there has been a lot of warming in the Indian and West Pacific. Does that heat get moved to the eastern Pacific, (is this through Kelvin waves?) and if so, is there any information/research on how often that moves? Also, is when that heat moves part of the spring prediction uncertainty barrier?

It is typical for above…

It is typical for above-average oceanic temperatures to reside in the western Pacific/Indonesia during La Nina (does not depend on MJO). As the event begins to fade, we would expect the warmth to start shifting eastward again, but this is part of a slower oceanic adjustment associated with transitions to ENSO-neutral. I'm not an expert in ocean dynamics, but I believe that ocean Kelvin waves have a role in this process. You're right that the spring uncertainty barrier may have some roots in the ocean-- more generally it exists in part because the spring is a transitional time of year for ENSO (events peak in the winter and then decay toward spring/summer) and the models sometimes have trouble forecasting the timing of those transitions and what is next.

La Nina's Effect on North Texas Summers

Michelle, as I've reported several years ago, La Ninas have led to many of the hottest summers on record in terms of 100-degree days in Dallas/Fort Worth: in 1954 (52), 1956 (48), 1998 (56 #3 hottest), 1999 (33), 2000 (46), 2006 (43), 2008 (30), 2011 (71 #1 hottest) and 2012 (34). However, we were lucky during the last two double-dip La Ninas in 2016-2017 and 2020-21 with fewer than 20 or even 10 or less a few of those years. Let's hope that holds true this summer!

outlook 2022

So guessing...would you say the next few months will be wetter/more snow and colder?

or just the opposite?

Not sure where you're…

Not sure where you're located, but CPC's outlook for March was released yesterday and is available here:

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/lead14/

Pacific Northwest

The relationship between precipitation and Nino 3.4 is not very convincing for the Pacific Northwest. Are there areas in the US or Americas that have a stronger correlation between the two?

You may find these maps …

You may find these maps (which are updated through Dec. 2021) to be helpful. In particular the column on the right shows how often (%) the precip anomaly (column on the left) occurs during an ENSO event. In general the wintertime precipitation signal for La Nina is stronger in the southern states (drier) than it is for the northern states (wetter), but there is still a decent relationship w/ PacNW experiencing wetter than average conditions about 60-70% of the time during La Nina.

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/ENSO/composites/EC_LNP_index.shtml

Not a slam dunk, which is why we encourage playing the long game.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/betting-climate-predictions

LA NINA

What affect does La Nina have over Nor Cal?

Good question. Here's a link…

Good question. Here's a link to a graphic showing the general precipitation/temperature patterns during winter for the US during La Nina (and El Nino).

https://www.climate.gov/media/13112

Far Northern California tends to see above-average precipitation though it all sort of depends on how you define northern California.

We're in for a dry year...

This year California has already gone through enough droughts and over usage of water. La Nina will make this worse. As in other comments, next season is way too soon. We need more time to prepare, and we need to stop using so much water. This is affecting both out bills and the amount of water that's available. With the amount of tourists, we are pushing the limit. This brings me to my next point. We need to find new ways to extract water, for pasteurization kits might not be enough. We also have so many people using gallons and gallons of water for showers, washing the dishes, and filling pools and draining them again. This is a serious problem, and it seems like nobody's addressing it. We better prepare for La Nina.

Comments have been disabled on this article